- INTRO

- Lectures XVIIe-XVIIIe

- Lectures XIXe-XXe

- 1820-1840

- 1840-1860

- 1860-1880

- 1880-1900

- 1900-1910

- 1910-1920

- 1920-1930

- 1920s

- Breton

- Tanguy - Ernst

- Eluard

- Jacob - Cocteau

- Gramsci - Lukacs

- Woolf

- Valéry

- Alain

- Mansfield

- Lawrence

- Bachelard

- Zweig

- Larbaud - Morand

- Hesse

- Döblin

- Musil

- Mann

- Colette

- Mauriac

- MartinDuGard

- Spengler

- Joyce

- Pabst

- S.Lewis

- Dreiser

- Pound

- Heisenberg

- Supervielle - Reverdy

- Sandburg

- Duhamel - Romains

- Giraudoux - Jouhandeau

- Cassirer

- Harlem - Langston Hughes

- Lovecraft

- Zamiatine

- Svevo - Pirandello

- TS Eliot

- Chesterton

- 1930-1940

- 1940-1950

- 1940s

- Chandler

- Sartre

- Beauvoir

- Mounier

- Borges

- McCullers - O'Connor

- Camus

- Cela

- Horkheimer - Adorno

- Bellows - Hopper - duBois

- Gödel

- Bogart

- Trevor

- Brecht

- Bataille - Michaux

- Merleau-Ponty - Ponge

- Simenon

- Aragon

- Mead - Benedict - Linton

- Wright

- Vogt - Asimov

- Orwell

- Buzzati - Pavese

- Lewin - Mayo - Maslow

- Algren - Irish

- Montherlant

- Fallada

- Malaparte

- 1950-1960

- 1950s

- Moravia

- Rossellini

- Nabokov

- Cioran

- Arendt

- Aron

- Marcuse

- Packard

- Wright Mills

- Vian - Queneau

- Quine - Austin

- Blanchot

- Sarraute - Butor - Duras

- Ionesco - Beckett

- Rogers

- Dürrenmatt

- Sutherland - Bacon

- Durrell - Murdoch

- Graham Greene

- Kawabata

- Kerouac

- Bellow - Malamud

- Martin-Santos

- Fanon - Memmi

- Riesman

- Böll - Grass

- Baldwin - Ellison

- Bergman

- Tennessee Williams

- Bradbury - A.C.Clarke

- Erikson

- Bachmann - Celan - Sachs

- Rulfo-Paz

- Carpentier

- Achébé - Soyinka

- Pollock

- Mishima

- Salinger - Styron

- Fromm

- 1960-1970

- 1960s

- Ricoeur

- Roth - Elkin

- Lévi-Strauss

- Burgess

- Pynchon - Heller - Toole

- Ellis

- U.Johnson - C.Wolf

- J.Rechy - H.Selby

- Antonioni

- T.Wolfe - N.Mailer

- Capote - Vonnegut

- Plath

- Burroughs

- Veneziano

- Godard

- Onetti - Sábato

- Sillitoe

- McCarthy - Minsky

- Sagan

- Gadamer

- Martin Luther King

- Laing

- P.K.Dick - Le Guin

- Lefebvre

- Althusser

- Lacan

- Foucault

- Jankélévitch

- Goffman

- Barthes

- Cortázar

- Grossman

- Warhol

- McLuhan

- 1970-1980

- 1980-1990

- 1990-2000

- Lectures XXIe

- Promenades

- Paysages

- Contact

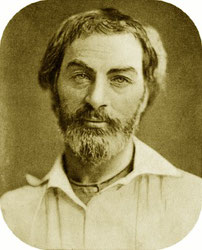

Walt Whitman (1819-1892), "Leaves of Grass" (1855) - Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), "I dwell in Possibility" (1862) - ......

Last update : 12/12/2019

Vers la fin du XIXe siècle, Walt Whitman et Emily Dickinson, en une décennie, vont poser dans le domaine de la littérature les fondations d'une tradition poétique américaine spécifique. Ces deux éminents poètes étaient on ne peut plus différents l'un de l'autre par leurs tempéraments et leurs styles - bien que, une fois de plus, on relève chez eux des influences d'Emerson et des transcendantalistes. Walt Whitman (1819-1892) était issu d'un milieu humble et dut travailler comme compositeur'typographe, instituteur itinérant, journaliste, infirmier volontaire pendant la guerre civile, puis, plus tard, comme clerc du gouvernement, et se fera connaître par "Leaves of Grass" conçut comme un poème épique américain : ce qui lui valut le titre de premier "poète de la démocratie" pour son inclusion de personnages allant du président à la prostituée. Cette oeuvre est aussi reconnu pour son usage de vers libres, de lignes de longueurs irrégulières et d'images et de symboles peu courants. Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), en revanche, passa sa vie dans la petite ville recluse et sans histoire d'Amherst, dans le Massachusetts, Elle ne se maria jamais et ne quitta que rarement sa chambre sur ses vieux jours, communiquant, dans la mesure où elle le faisait, uniquement par lettre. Elle semble avoir réservé toute son énergie émotionnelle pour les 1800 poèmes quelle écrivit - dont seulement une douzaine fut publiée de son vivant, les autres restant privés. L'influence du Transcendantalisme est évidente, mais elle alla bien au-delà, explorant des thèmes comme la mort, la mélancolie, les sexes et la religion (tirant du Nouveau Testament des histoires en américain populaire), Du point de vue technique, son oeuvre était en avance sur son temps, peut-être même proto-moderniste, employant ponctuation, capitales, longueurs de ligne et ruptures singulières et ne donnant souvent pas de titre à ses poèmes....

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

"Re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem

and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body" - Considéré

comme le plus grand poète américain et, à bien des égards, comme le plus énigmatique, Walt Whitman a contribué au mouvement transcendantaliste."Song of Myself" met l'accent sur un individualisme

qui a pour finalité de s'unir à toutes autres personnes par un lien transcendantal.

Walt Whitman est né à West Hills, un village près de Hempstead à Long Island, New York, fils de Louisa van Velsor, dont il restera très proche toute sa vie,

et de Walter Whitman, agriculteur et menuisier. Mais il n'apparut sur la scène du monde littéraire qu'en 1855, à 36 ans, l'année où il publia "Leaves of Grass". Jusque-là, autodidacte, il fut

professeur sans prétention, écrivain sans succès, auteurs d'articles de journaux sans prétention, typographe puis charpentier encadrant des maisons de deux et trois pièces à Brooklyn. Whitman

était volontiers décrit comme un iconoclaste, innovant en utilisant le vers libres, philosophant sur diverses questions telles que la démocratie, la guerre, la politique, la race et l'esclavage,

célébrant la patrie, la nature, l'amour homosexuel.

Whitman semble avoir compris, comme Emerson, qu'ils vivent une toute nouvelle expérience, le renouveau de la démocratie dans le monde moderne : les

aristocraties du Massachusetts et de la Virginie ont pu ouvrir le chemin, mais ils ne peuvent contrôler cette nation dont s'emparent les peuples par la force du nombre. Emerson attend un poète

qui révèle cette nouvelle vie américaine, ces nouvelles possibilités humaines : "Our logrolling, our stumps and their politics, our fisheries, our Negroes, and Indians, our boasts, and our

repudiations, the wrath of rogues, and the pusillanimity of honest men, the northern trade, the southern planting, the western clearing, Oregon, and Texas, are yet unsung.."

Profondément affecté par les drames de la Guerre de Sécession (1861-1865), Whitman écrivit de nombreux poèmes pendant cette période, notamment dans Drum

Taps (1865). Louisa May Alcott avait également été une infirmière dévouée et écrivit ses Hospital Sketches (1863), tandis que Whitman écrivit Memoranda During the War (1875), et un hommage au

président Abraham Lincoln à l'annonce de sa mort. Whitman publie en 1867 sa quatrième édition de Leaves of Grass, puis une cinquième édition en 1870. La version finale de Leaves of Grass, connue

sous le nom de "death-bed edition" paraît en 1891...

"Leaves of Grass" (Feuilles d'herbe, 1855)

Leaves of Grass est à la fois le titre du premier recueil de poèmes publié par Walt Whitman en 1855, mais aussi le titre du dernier livre de poèmes publié

avant sa mort en 1892, et de cinq autres éditions publiées de son vivant. A chaque édition ultérieure du livre, à partir de son socle initial de douze poèmes, le poète a ajouté, modifié ou

supprimé de nouveaux poèmes, révélant ainsi l'évolution de ses préoccupations au fil du temps, toute une chronologie de sa vie. La troisième édition intègre par exemple 146 poèmes, ses amours

homosexuels et son pessimisme devant le tragique de la guerre de Sécession. La version de 1881, Whitman avait 62 ans, fut poursuivi pour obscénité par le procureur du district. La dernière

version de Leaves of Grass à paraître du vivant de Whitman ne contenait que des corrections mineures par rapport à l'édition de 1882 : "L. of G. at last complete, écrit-il, after 33 y'rs of

hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old — the wonder to me that I have carried it on to accomplish

as essentially as it is, tho' I see well enough its numerous deficiencies & faults."...

Le premier poème du recueil, "Poem of Walt Whitman, an American", prend pour titre "Song of Myself" en 1881. Pour Whitman, toute poésie a pour origine le moi, et la meilleure façon de créer de la poétique est tout simplement de s'abandonner à l'observation du fonctionnement de son esprit contemplant la nature et tissant les relations symboliques qui donnent sens à notre appartenance au monde...

"I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air,

Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death.

Creeds and schools in abeyance,

Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten,

I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard,

Nature without check with original energy.

Houses and rooms are full of perfumes, the shelves are crowded with perfumes,

I breathe the fragrance myself and know it and like it,

The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not let it.

The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of the distillation, it is odorless,

It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

The smoke of my own breath,

Echoes, ripples, buzz’d whispers, love-root, silk-thread, crotch and vine,

My respiration and inspiration, the beating of my heart, the passing of blood and air through my lungs,

The sniff of green leaves and dry leaves, and of the shore and dark-color’d sea-rocks, and of hay in the barn,

The sound of the belch’d words of my voice loos’d to the eddies of the wind,

A few light kisses, a few embraces, a reaching around of arms,

The play of shine and shade on the trees as the supple boughs wag,

The delight alone or in the rush of the streets, or along the fields and hill-sides,

The feeling of health, the full-noon trill, the song of me rising from bed and meeting the sun.

Have you reckon’d a thousand acres much? have you reckon’d the earth much?

Have you practis’d so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun, (there are millions of suns left,)

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the spectres in

books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self."

Le poème recèle des épisodes clés. Ainsi, l'herbe, "Qu'est-ce que l'herbe ?" (“What is the grass?”) demande un enfant au narrateur, dans la sixième section du poème. Au narrateur de s'expliquer, de justifier sa symbolique. Whitman dit qu'il ne sait pas plus que l'enfant ce qu'est l'herbe dans son essence. Mais cette herbe qui pousse un peu partout et se nourrit des corps des morts, est tout autant signe de la régénération de la nature que symbole du lien entre tous les hommes, symbole ultime de la démocratie, l'herbe est le signe de l'égalité. Si nous sommes des gens ordinaires et des hommes d'État distingués, nous ne sommes que des brins d'herbe, ni plus ni moins. Nous sommes tous issus de la nature, et à la nature, l'herbe, nous retournerons. Et plus encore, plus paradoxal, en nous affirmant comme n'étant que des feuilles ou des herbe, nous devenons plus que des feuilles ou des herbes individuelles, nous devenons une partie de cette belle unité, le champ de verdure, la colline ondoyante, la Nation.. Walt Whitman nous livre ainsi une première expérience de pensée...

"A child said What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands;

How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any more than he.

I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green stuff woven.

Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may see and remark, and say Whose?

Or I guess the grass is itself a child, the produced babe of the vegetation.

Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic,

And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same.

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.

Tenderly will I use you curling grass,

It may be you transpire from the breasts of young men,

It may be if I had known them I would have loved them,

It may be you are from old people, or from offspring taken soon out of their mothers’ laps,

And here you are the mothers’ laps.

This grass is very dark to be from the white heads of old mothers,

Darker than the colorless beards of old men,

Dark to come from under the faint red roofs of mouths.

O I perceive after all so many uttering tongues,

And I perceive they do not come from the roofs of mouths for nothing.

I wish I could translate the hints about the dead young men and women,

And the hints about old men and mothers, and the offspring taken soon out of their laps.

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceas’d the moment life appear’d.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

Dans la onzième section du poème, le célèbre "twenty-ninth bather" montre une femme regardant vingt-huit jeunes hommes se baigner dans l'océan, la voici fantasmant, espérant les rejoindre : pour faire véritablement l'expérience du monde, il faut plonger en lui, ' l'expérience sensuelle d'un vingt-neuvième baigneur -, tout en restant suffisamment distinct pour conserver une certaine perspective, et rester invisible pour ne rien troubler....

"Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore,

Twenty-eight young men and all so friendly;

Twenty-eight years of womanly life and all so lonesome.

She owns the fine house by the rise of the bank,

She hides handsome and richly drest aft the blinds of the window.

Which of the young men does she like the best?

Ah the homeliest of them is beautiful to her.

Where are you off to, lady? for I see you,

You splash in the water there, yet stay stock still in your room.

Dancing and laughing along the beach came the twenty-ninth bather,

The rest did not see her, but she saw them and loved them.

The beards of the young men glisten’d with wet, it ran from their long hair,

Little streams pass’d all over their bodies.

An unseen hand also pass’d over their bodies,

It descended tremblingly from their temples and ribs.

The young men float on their backs, their white bellies bulge to the sun, they do not ask who seizes fast to them,

They do not know who puffs and declines with pendant and bending arch,

They do not think whom they souse with spray."

Dans la vingt-cinquième section, le poète fusionne avec la nature, communie avec chaque être humain, encore faut-il pouvoir transmettre ces expériences successives, souvent intenses, troublantes, sans les falsifier ou les restreindre : "la parole est la jumelle de ma vision, elle est inégale pour se mesurer, Elle me provoque à jamais, dit-il sarcastiquement, Walt tu en as assez, pourquoi ne pas la laisser sortir alors ? Ayant déjà établi qu'il peut avoir une expérience d'harmonie lorsqu'il rencontre d'autres personnes ("Je ne demande pas à la personne blessée comment elle se sent, je deviens moi-même la personne blessée"), il doit trouver un moyen de retransmettre cette expérience sans la falsifier ou la diminuer. Résistant aux réponses faciles, il jure par la suite qu'il ne livrera jamais à aucune interprétation...

"Dazzling and tremendous how quick the sun-rise would kill me,

If I could not now and always send sun-rise out of me.

We also ascend dazzling and tremendous as the sun,

We found our own O my soul in the calm and cool of the daybreak.

My voice goes after what my eyes cannot reach,

With the twirl of my tongue I encompass worlds and volumes of worlds.

Speech is the twin of my vision, it is unequal to measure itself,

It provokes me forever, it says sarcastically,

Walt you contain enough, why don’t you let it out then?

Come now I will not be tantalized, you conceive too much of articulation,

Do you not know O speech how the buds beneath you are folded?

Waiting in gloom, protected by frost,

The dirt receding before my prophetical screams,

I underlying causes to balance them at last,

My knowledge my live parts, it keeping tally with the meaning of all things,

Happiness, (which whoever hears me let him or her set out in search of this day.)

My final merit I refuse you, I refuse putting from me what I really am,

Encompass worlds, but never try to encompass me,

I crowd your sleekest and best by simply looking toward you.

Writing and talk do not prove me,

I carry the plenum of proof and every thing else in my face,

With the hush of my lips I wholly confound the skeptic.

Et voici le poète s'aba,donnat par exemple aux bruits du monde,

"Now I will do nothing but listen,

To accrue what I hear into this song, to let sounds contribute toward it.

I hear bravuras of birds, bustle of growing wheat, gossip of flames, clack of sticks cooking my meals,

I hear the sound I love, the sound of the human voice,

I hear all sounds running together, combined, fused or following,

Sounds of the city and sounds out of the city, sounds of the day and night,

Talkative young ones to those that like them, the loud laugh of work-people at their meals,

The angry base of disjointed friendship, the faint tones of the sick,

The judge with hands tight to the desk, his pallid lips pronouncing a death-sentence,

The heave’e’yo of stevedores unlading ships by the wharves, the refrain of the anchor-lifters,

The ring of alarm-bells, the cry of fire, the whirr of swift-streaking engines and hose-carts with premonitory tinkles and color’d

lights,

The steam whistle, the solid roll of the train of approaching cars,

The slow march play’d at the head of the association marching two and two,

(They go to guard some corpse, the flag-tops are draped with black muslin.)

I hear the violoncello, (’tis the young man’s heart’s complaint,)

I hear the key’d cornet, it glides quickly in through my ears,

It shakes mad-sweet pangs through my belly and breast.

I hear the chorus, it is a grand opera,

Ah this indeed is music—this suits me.

A tenor large and fresh as the creation fills me,

The orbic flex of his mouth is pouring and filling me full.

I hear the train’d soprano (what work with hers is this?)

The orchestra whirls me wider than Uranus flies,

It wrenches such ardors from me I did not know I possess’d them,

It sails me, I dab with bare feet, they are lick’d by the indolent waves,

I am cut by bitter and angry hail, I lose my breath,

Steep’d amid honey’d morphine, my windpipe throttled in fakes of death,

At length let up again to feel the puzzle of puzzles,

And that we call Being."

Dans "I Sing the Electric Body", - apparu comme Poem of the Body dans l'édition de 1856 de Leaves of Grass, puis incorporé dans la séquence Children of

Adam (1867) -, le poète exhorte ses lecteurs à s'affranchir de toute honte envers leur corps et de laisser libre cours à leurs instincts de communion, soulevant peut-être la question

de son homosexualité et l'horreur que lui inspirait l'esclavage. Pourquoi "électrique"? Parce que le corps s'anime, comme électrifié par la manière dont ses composantes interagissent entre elles,

que l'interaction soit explicite ou implicite, et par la manière dont les corps interagissent entre eux, dans le respect mutuel ou dans l'exploitation. "Et si le corps n'était pas l'âme,

qu'est-ce que l'âme ?" (“And if the body were not the soul, what is the soul?”) est ici la question centrale, et si le poète n'y répond pas directement, c'est toute expérience aussi

métaphysique que charnelle qu'il livre du corps, "The curious sympathy one feels when feeling with the hand the naked meat of the body"....

"Les armées de ceux que j'aime m'engendre et je les engendre, Elles ne me laisseront pas partir tant que je ne les aurai pas accompagnées, que je ne leur

aurai pas répondu, et que je ne les aurai pas troublées, et que je ne les aurai pas chargées de la charge de l'âme."

"I sing the body electric,

The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them,

They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,

And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul.

Was it doubted that those who corrupt their own bodies conceal themselves?

And if those who defile the living are as bad as they who defile the dead?

And if the body does not do fully as much as the soul?

And if the body were not the soul, what is the soul?

The love of the body of man or woman balks account, the body itself balks account,

That of the male is perfect, and that of the female is perfect.

The expression of the face balks account,

But the expression of a well-made man appears not only in his face,

It is in his limbs and joints also, it is curiously in the joints of his hips and wrists,

It is in his walk, the carriage of his neck, the flex of his waist and knees, dress does not hide him,

The strong sweet quality he has strikes through the cotton and broadcloth,

To see him pass conveys as much as the best poem, perhaps more,

You linger to see his back, and the back of his neck and shoulder-side.

The sprawl and fulness of babes, the bosoms and heads of women, the folds of their dress, their style as we pass in the street, the contour of their

shape downwards,

The swimmer naked in the swimming-bath, seen as he swims through the transparent green-shine, or lies with his face up and rolls silently to and fro in

the heave of the water,

The bending forward and backward of rowers in row-boats, the horseman in his saddle,

Girls, mothers, house-keepers, in all their performances,

The group of laborers seated at noon-time with their open dinner-kettles, and their wives waiting,

The female soothing a child, the farmer’s daughter in the garden or cow-yard,

The young fellow hoeing corn, the sleigh-driver driving his six horses through the crowd,

The wrestle of wrestlers, two apprentice-boys, quite grown, lusty, good-natured, native-born, out on the vacant lot at sun-down after

work,

The coats and caps thrown down, the embrace of love and resistance,

The upper-hold and under-hold, the hair rumpled over and blinding the eyes;

The march of firemen in their own costumes, the play of masculine muscle through clean-setting trowsers and waist-straps,

The slow return from the fire, the pause when the bell strikes suddenly again, and the listening on the alert,

The natural, perfect, varied attitudes, the bent head, the curv’d neck and the counting;

Such-like I love—I loosen myself, pass freely, am at the mother’s breast with the little child,

Swim with the swimmers, wrestle with wrestlers, march in line with the firemen, and pause, listen, count."

"A Noiseless Patient Spider" - Dernier poème et court poème, très sombre, de Walt Whitman, publié dans l'édition de 1891 de Leaves of Grass, exprime toute la difficulté de l'existence humaine, le sentiment de désespoir qu'elle peut emporter, "une araignée patiente et silencieuse", solitaire, semblant abandonnée sans vie dans la fascination des "océans infinis de l'univers".... Il a lancé un filament, un filament, un filament, hors de lui-même, Et toi, ô mon âme, là où tu te trouves, Entouré, détaché, dans des océans d'espace sans mesure, Sans cesse, rêve, s'aventure, explore, cherche les sphères qui les relient, jusqu'à ce que l'ancre se stabilise, Jusqu'à ce que le fil de soie que tu jettes s'accroche quelque part, ô mon âme....

"A noiseless patient spider,

I mark’d where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark’d how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form’d, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul."

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

L'œuvre de la poétesse américaine Emily Dickinson ne fut véritablement connue qu'à partir des années 1950, n'ayant publié de son vivant que cinq poèmes qui

passèrent inaperçus. Son oeuvre intensément personnelle rejoint cette génération d'écrivains, tels que Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau et Walt Whitman, qui expérimentent le langage,

l'expression, afin de les libérer des contraintes conventionnelles, qui atteignent les limites inéluctables de leurs sociétés et s'engagent dans un désir d'évasions imaginables. Emily Elizabeth

Dickinson est née à Amherst, Massachusetts, son père était un jeune avocat ambitieux et un citoyen exemplaire devenu représentant du Massachusetts au Congrès américain en 1852.

La vie d'Emily Dickinson se déroulera toute entière à Amherst, élevée dans la religion congrégationaliste, puis après des études à Amherst College, puis à Mount Holyoke Seminary (une seule année), se cloîtra chez son père et vivra en recluse excentrique, vêtue de blanc, soignant son personnage et ses apparitions, écrivant des poèmes qu'elle montre à quelques intimes, puis qu'elle dissimule dans un coffre. Le monde qui l'entoure est encore très puritain mais la jeune poétesse, malgré ses angoisses métaphysiques, ne franchira pas le seuil de cette orthodoxie religieuse.

Contrairement à Emerson ou à Whitman, la nature n'est, pour Emily Dickinson, qu'illusion fugitive et brillante, sa poétique privilégie l'exploration psychologique de sa solitude existentielle, ponctuée de quelques vains appels passionnés, une solitude hantée par la mort et des hallucinations qui débouchent sur des métaphores d'une étrange singularité. Etrange singularité, parce que la poétesse ne puise pas dans la religion, dans le puritanisme ou dans le Revivalisme ambiant ("Escape is such a thankful Word", écrit-elle en 1875), ses obsessions, "comme ce monde se sent seul, quelque chose d'aussi désolant s'insinue dans l'esprit et nous ne connaissons pas son nom, et il ne disparaîtra pas, soit que le ciel semble plus grand, soit que la Terre soit beaucoup plus petite, soit que Dieu soit plus "Notre Père" et que nous sentions notre besoin augmenter"...

"How lonely this world is growing, something so desolate creeps over the spirit and we don’t know its name, and it won’t go away, either Heaven is seeming greater, or Earth a great deal more small, or God is more ‘Our Father,’ and we feel our need increased. Christ is calling everyone here, all my companions have answered, even my darling Vinnie believes she loves, and trusts him, and I am standing alone in rebellion, and growing very careless. Abby, Mary, Jane, and farthest of all my Vinnie have been seeking, and they all believe they have found; I can’t tell you what they have found, but they think it is something precious. I wonder if it is?"

... la poésie est plus essentielle que la religion, l'imaginaire qu'elle reconstruit et exprime formellement via un vocabulaire d'une grande richesse, parfois inattendu ("I have dared to do strange things - bold things"), et une métrique souvent hymnique. Recluse, la fin des années 1850 marque le début de la plus grande période poétique d'Emily Dickinson,

" Charm invests a face / Imperfectly beheld / The Lady dare not lift her Vail / For fear it be dispelled / But peers beyond her mesh / And wishes – and denies / Lest interview – annul a want – / That Image – satisfies - "

... en 1865, elle avait écrit près de 1 100 poèmes, exprimant la douleur, le chagrin, la joie, l'amour, la nature. Après avoir affronté la mort de son père en 1874, l'attaque de sa mère en 1875, Emily Dickinson est morte à Amherst en 1886, à 55 ans. Après sa mort, les membres de sa famille ont trouvé ses livres cousus à la main, ou "fascicles", qui contenaient près de 1 800 poèmes. Une première sélection de ses poèmes sera publiée en 1890. Dans le centre d'Amherst, Massachusetts, "Emily Dickinson Museum" comprend deux maisons historiques, The Dickinson Homestead, où naquit et mourut Emily Elizabeth Dickinson, et The Evergreens, où vécurent son frère et sa femme, Austin et Susan Dickinson. Quant à sa poésie, elle ne cesse de nous dire que le chemin qu'elle emprunte ne peut être cette route rectiligne qui mène à la vérité ou à quelque certitude, elle se vit dans l'instant et le reflète intensément...

"Tell all the truth but tell it slant" (1868)

"Tell all the truth but tell it slant

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind.."

"I dwell in Possibility" (1862), enfermée dans sa solitude, recluse dans The Homestead, Emily Dickinson puise dans le cercle limité de sa chambre les immenses possibilités que lui offre la poésie, J'habite dans les Possibilités, Une maison plus adaptée que la prose, Plus de fenêtres et plus de portes...

"I dwell in Possibility

A fairer House than Prose

More numerous of Windows

Superior - for Doors

Of Chambers as the Cedars

Impregnable of Eye

And for an Everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky

Of Visitors - the fairest

For Occupation – This

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise"

"Wild Nights – Wild Nights!" (1861), portrait de la solitude et de la si sauvage tentation amoureuse, un poème qui rompt avec les autres oeuvres d'Emily Dickinson et nous suggère un autre visage du poète : le film "Wild Nights with Emily", réalisé par Madeleine Olnek (2018), avec Molly Shannon et Susan Ziegler, exploitera cette éventualité en mettant en scène les troubles relations supposées d'Emily et de Susan Gilbert Dickinson (1830-1913), sa belle-soeur, "Dollie", femme intellectuelle et charismatique que la poète rencontra lorsqu'elle avait 20 ans et qui fut en quelque sorte sa muse : "Qui t’aime le plus, et t’aime le mieux, et pense à toi quand les autres dorment oublieux ?", lui écrira-telle en février 1852. Susan Dickinson a reçu plus de 250 poèmes tout au long des quarante années que partagèrent les deux femmes et leur correspondance intime a fait l'objet de nombreuses exégèses...

Wild Nights – Wild Nights!

Were I with thee

Wild Nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile – the Winds –

To a Heart in port –

Done with the Compass –

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden –

Ah, the Sea!

Might I but moor – Tonight –

In Thee!

"It was not Death, for I stood up" (1862), Emily Dickinson confrontée à la pensée de la mort, de cette mort qui l'obsède et qui tente de la définir, de la définir en elle par rapport à ce qu'elle n'est pas, Ce n'était pas la mort, car je me suis levé, Ce n'était pas la nuit, pour toutes les cloches entendues, Ce n'était pas la froidure, car sur mon corps, j'ai ressenti la chaleur du souffle de l'air...

It was not Death, for I stood up,

And all the Dead, lie down

It was not Night, for all the Bells

Put out their Tongues, for Noon.

It was not Frost, for on my Flesh

I felt Siroccos– crawl

Nor Fire– for just my Marble feet

Could keep a Chancel, cool

And yet, it tasted, like them all,

The Figures I have seen

Set orderly, for Burial,

Reminded me, of mine

As if my life were shaven,

And fitted to a frame,

And could not breathe without a key,

And 'twas like Midnight, some

When everything that ticked– has stopped

And Space stares– all around

Or Grisly frosts– first Autumn morns,

Repeal the Beating Ground

But, most, like Chaos– Stopless– cool

Without a Chance, or Spar

Or even a Report of Land

To justify– Despair.

"Before I got my eye put out" (1862), Emily Dickinson fut dans l'obligation, lorsqu'elle atteignit la trentaine, de consulter le principal ophtalmologue de Boston. Particulièrement sensibles à la lumière, parfois contrainte de ne pouvoir ni lire ni écrire, c'est avec le regard de l'âme et d'une autre expérience de la lumière qu'elle se livre ici, Voir le ciel pour elle-même....

Before I got my eye put out–

I liked as well to see

As other creatures, that have eyes–

And know no other way–

But were it told to me, Today,

That I might have the Sky

For mine, I tell you that my Heart

Would split, for size of me–

The Meadows– mine –

The Mountains– mine –

All Forests– Stintless stars–

As much of noon, as I could take–

Between my finite eyes–

The Motions of the Dipping Birds–

The Morning’s Amber Road–

For mine– to look at when I liked,

The news would strike me dead–

So safer– guess– with just my soul

Opon the window pane

Where other creatures put their eye –

Incautious– of the Sun–

"After great pain, a formal feeling comes" (1862), Emily Dickinson n'exprime pas ici le chagrin ou la peine, mais le sentiment qui s'ensuit et toutes les nuances émotionnelles que suscitent cette expérience de l'après, la désorientation, 'Heure de plomb, le froid, la stupeur, puis le laisser aller...

"After great pain, a formal feeling comes–

The Nerves sit ceremonious, like tombs–

The stiff Heart questions "was it He, that bore,

And "Yesterday, or Centuries before"?

The Feet, mechanical, go round–

A Wooden way

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought–

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone–

This is the Hour of Lead–

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the snow–

First– Chill– then stupor– then the letting go."

"Because I could not stop for Death" (1863), Emily Dickinson affronte sa propre mort, une mort vécue par petits détails extérieurs, nulle question à se poser, nulle exigence à formuler, lentement, inexorablement, le chemin semble mener à quelque sentiment d'éternité....

"Because I could not stop for Death–

He kindly stopped for me–

The Carriage held but just Ourselves–

And Immortality.

We slowly drove– He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility–

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess– in the Ring–

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain–

We passed the Setting Sun–

Or rather– He passed Us–

The Dews drew quivering and Chill–

For only Gossamer, my Gown–

My Tippet– only Tulle–

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground–

The Roof was scarcely visible–

The Cornice– in the Ground–

Since then– 'tis Centuries– and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses' Heads

Were toward Eternity."