- INTRO

- Lectures XVIIe-XVIIIe

- Lectures XIXe-XXe

- 1820-1840

- 1840-1860

- 1860-1880

- 1880-1900

- 1900-1910

- 1910-1920

- 1920-1930

- 1920s

- Breton

- Tanguy - Ernst

- Eluard

- Jacob - Cocteau

- Gramsci

- Lukacs

- Hesse

- Woolf

- Valéry

- Alain

- Mansfield

- Lawrence

- Bachelard

- Zweig

- Larbaud - Morand

- Döblin

- Musil

- Mann

- Colette

- Mauriac

- MartinDuGard

- Spengler

- Joyce

- Pabst

- S.Lewis

- Dreiser

- Pound

- Heisenberg

- TS Eliot

- Supervielle - Reverdy

- Sandburg

- Duhamel - Romains

- Giraudoux - Jouhandeau

- Svevo - Pirandello

- Harlem - Langston Hughes

- Cassirer

- Lovecraft

- Zamiatine

- W.Benjamin

- Chesterton

- Akutagawa

- Tanizaki

- 1930-1940

- 1930s

- Fitzgerald

- Hemingway

- Faulkner

- Koch

- Céline

- Bernanos

- Jouve

- DosPassos

- Kojève

- Miller-Nin

- Grosz - Dix

- Green

- Ortega y Gasset

- Wittgenstein

- Russell - Carnap

- Artaud

- Jaspers

- Sapir - Piaget

- Guillén

- Garcia Lorca

- Hammett

- A.Christie

- Heidegger

- Icaza

- Huxley

- Hubble

- Caldwell

- Steinbeck

- Waugh

- Blixen

- Rhys

- J.Roth - Doderer

- Aub

- Malraux-StExupéry

- DBarnes-NWest

- 1940-1950

- 1940s

- Chandler

- Sartre

- Beauvoir

- Mounier

- Borges

- McCullers

- Camus

- Horkheimer - Adorno

- Cela

- Wright

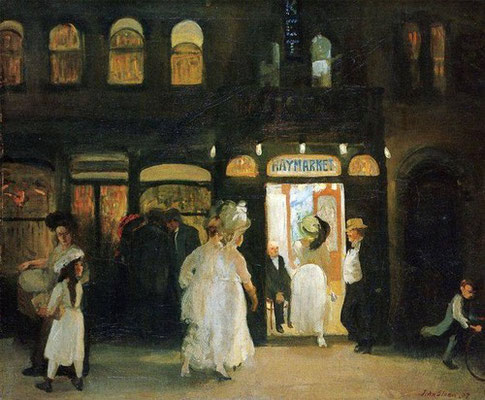

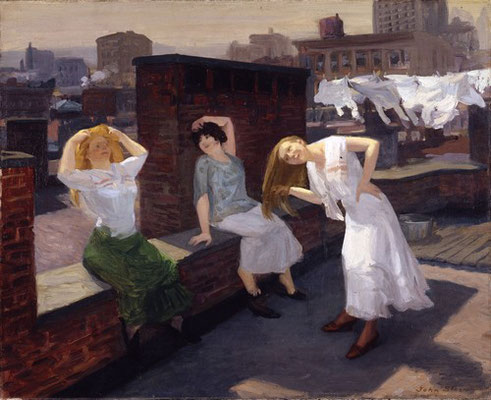

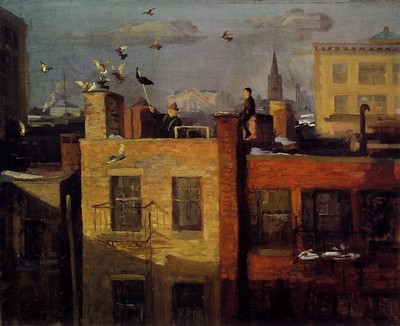

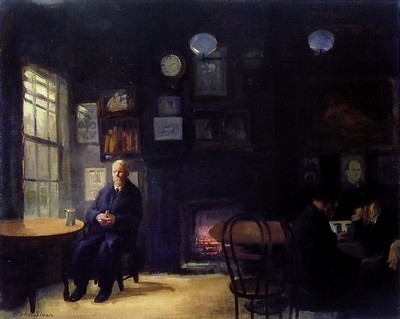

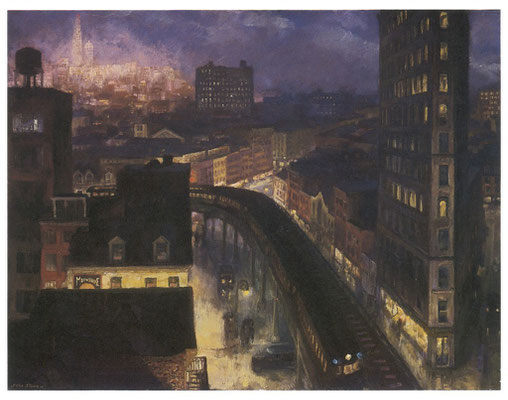

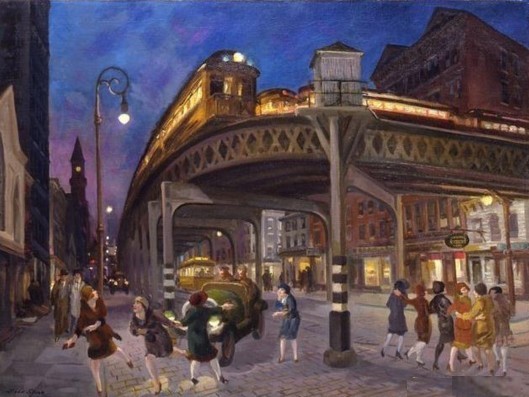

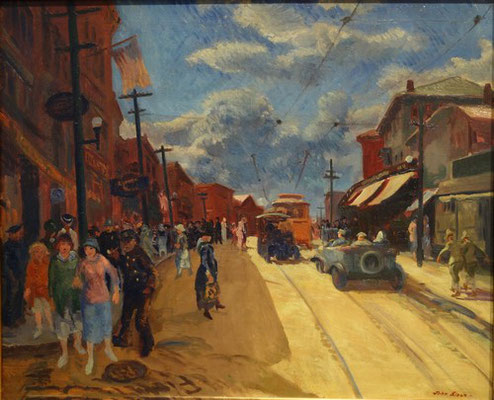

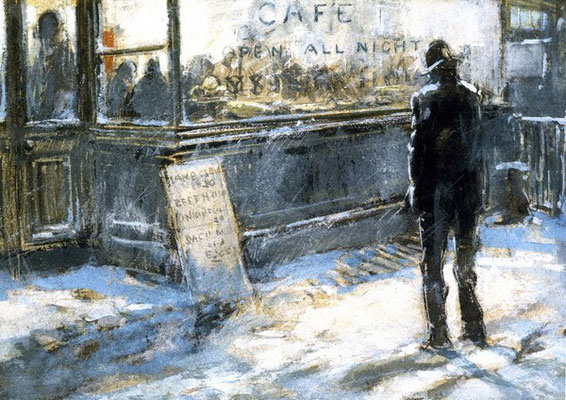

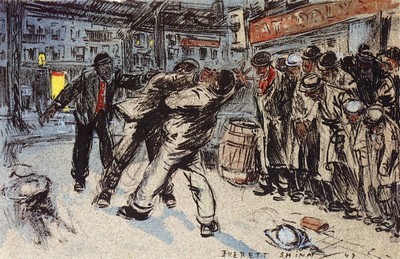

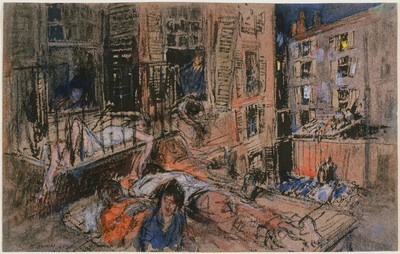

- Bellows - Hopper - duBois

- Gödel - Türing

- Bataille - Michaux

- Bogart

- Trevor

- Brecht

- Merleau-Ponty - Ponge

- Simenon

- Aragon

- Algren - Irish

- Bloch

- Mead - Benedict - Linton

- Vogt - Asimov

- Orwell

- Montherlant

- Lewin - Mayo - Maslow

- Buzzati - Pavese

- Vittorini

- Fallada

- Malaparte

- Canetti

- Lowry - Bowles

- Koestler

- Welty

- Boulgakov

- Tamiki - Yôkô

- Weil

- Gadda

- 1950-1960

- 1950s

- Moravia

- Rossellini

- Nabokov

- Cioran

- Arendt

- Aron

- Marcuse

- Packard

- Wright Mills

- Vian - Queneau

- Quine - Austin

- Blanchot

- Sarraute - Butor - Duras

- Ionesco - Beckett

- Rogers

- Dürrenmatt

- Sutherland - Bacon

- Peake

- Durrell - Murdoch

- Graham Greene

- Kawabata

- Kerouac

- Bellow - Malamud

- Martin-Santos

- Fanon - Memmi

- Riesman

- Böll - Grass

- Ellison

- Bergman

- Baldwin

- Fromm

- Bradbury - A.C.Clarke

- Tennessee Williams

- Erikson

- Bachmann - Celan - Sachs

- Rulfo-Paz

- Achébé - Soyinka

- Pollock

- Carpentier

- Mishima

- Salinger - Styron

- Pasternak

- Asturias

- O'Connor

- 1960-1970

- 1960s

- Abe

- Ricoeur

- Roth - Elkin

- Lévi-Strauss

- Burgess

- U.Johnson - C.Wolf

- Heller - Toole

- Naipaul

- J.Rechy - H.Selby

- Antonioni

- T.Wolfe - N.Mailer

- Capote - Vonnegut

- Plath

- Burroughs

- Veneziano

- Godard

- Onetti - Sábato

- Sillitoe

- McCarthy - Minsky

- Sagan

- Gadamer

- Martin Luther King

- Laing

- P.K.Dick - Le Guin

- Lefebvre

- Althusser

- Lacan

- Foucault

- Jankélévitch

- Goffman

- Barthes

- Cortázar

- Warhol

- Dolls

- Berne

- Grossman

- McLuhan

- Soljénitsyne

- Lessing

- Leary

- Kuhn

- Ellis

- HarperLee

- 1970-1980

- 1970s

- Habermas

- Handke

- GarciaMarquez

- Deleuze

- Derrida

- Beck

- Satir

- Kundera

- Hrabal

- Didion

- Guinzbourg

- Lovelock

- Vietnam

- H.S.Thompson - Bukowski

- Pynchon

- E.T.Hall

- Bateson - Watzlawick

- Carver

- Irving

- Milgram

- VargasLlosa

- Puig - Donoso

- Lasch-Sennett

- Crozier - Touraine

- Friedan-Greer

- Jacob-Monod

- Dawkins

- Beattie - Phillips

- Gaddis

- Rawls

- Zinoviev

- H.Searles

- Ballard

- Jong

- Kôno

- Calvino

- 1980-1990

- 1990-2000

- Lectures XXIe

- Promenades

- Paysages

- Contact

IdaTarbell (1857 -1944), "The History of the Standard Oil Company" (1904) - Upton Sinclair (1878-1968), "The Jungle" (1906) - Stephen Crane (1871-1900), "Maggie, a Girl of the Streets (1893), "The Red Badge of Courage" (1895) - Frank Norris (1870-1902), "McTeague: A Story of San Francisco" (1899), "The Octopus: A California Story" (1901) - Jacob Riis (1849-1914) - ...

Last update: 11/11/2016

"Our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner, for the kind of influence he exercises.." He? - C'est en 1904 que Ida Tarbell (1857 -1944) est devenue l'une des muckrakers (journalistes d'investigation) les plus influentes de ce "capitalisme de l'âge d'or" (Gilded Age, 1877-1896) avec la publication de son célèbre, et désormais classique, "The History of the Standard Oil Company". Ce "capitalisme de l'âge d'or" fut suivi par réaction par ce qu'on a appelé, aux Etats-Unis, "The Progressive Era" (1896–1917), une période d'activisme social et de réforme politique axée sur la lutte contre la corruption, le monopole, le gaspillage et l'inefficacité - avant que ne s'impose un retournement lorsque prit fin lors de l'engagement américain dans la Première Guerre mondiale (1917-1918), qu'implosent sans les années 1920.

Un "classique" du journalisme d'investigation : Tarbell avait mis au jour, minutieusement, des documents internes, étayés par des entretiens avec des employés, des avocats et - avec l'aide de Mark Twain - des conversations "naïvement menées" avec le cadre supérieur le plus puissant de Standard Oil à l'époque, Henry H. Rogers. Elle avait, dans sa jeunesse, été témoin de la "guerre du pétrole" de 1872 et du massacre de Cleveland, au cours duquel des dizaines de petits producteurs de pétrole de l'Ohio et de la Pennsylvanie occidentale, dont son père, avaient été confrontés à un choix décourageant qui semble venir de nulle part, vendre leur entreprise à John D. Rockefeller, Sr., 32 ans ("It takes time to crush men who are pursuing legitimate trade. But one of Mr. Rockefeller’s most impressive characteristics is patience"), et à sa Standard Oil Company nouvellement constituée, ou courir à la ruine. S.S. McClure, fondateur du magazine McClure's, l'engagera en 1894, publiera en feuilleton l'un des comptes rendus les plus complets de l'ascension du monopole commercial que constituait la Standard Oil Company et son utilisation de pratiques déloyales. Une Standard Oil, qui sera par suite jugée en violation de la loi antitrust Sherman et dissoute (1911).

Ces articles contribuèrent à définir une tendance croissante à l'investigation, à l'exposé et à la croisade dans les journaux libéraux de l'époque, une technique que le président américain Theodore Roosevelt qualifia en 1906 de "muckraking". L'association de Tarbell avec McClure's a duré jusqu'en 1906. Son autobiographie, "All in the Day's Work", a été publiée en 1939...

Upton Sinclair est apparu sur la scène américaine vers 1906. Il avait écrit et publié cinq romans sans faire véritablement impression en tant que romancier. Puis il passa sept semaines dans le quartier des parcs à bestiaux de Chicago à l'automne 1904, où il a parlé avec des ouvriers, des patrons, des surintendants, des gardiens de nuit, des tenanciers de saloon, des membres du clergé et maintes catégories de travailleurs. En 1905, commence à paraître, dans un hebdomadaire socialiste, the Appeal to Reason, un roman sur les abattoirs de Chicago, de cet auteur presque inconnu : "The Jungle". Le roman est présenté au grand public américain sous forme de livre en 1906. Le succès est immédiat et énorme. Il est devenu un "best-seller" en Amérique, en Angleterre et dans les colonies britanniques. Il est traduit en dix-sept langues, et le monde prend conscience que l'Amérique industrielle, dans son labeur, sa misère et son espoir, a trouvé une voix. "The Jungle" a été le point culminant du mouvement littéraire américain qui s'est intéressé à l'étude et à la dénonciation des maux des grandes entreprises. Les articles et les livres ont suscité la peur et la colère des grands intérêts commerciaux.

Ce jeune homme, Upton Sinclair, en écrivant un livre, a placé la grande industrie sur la défensive qui, immédiatement, a réagi en décidant de resserrer son emprise sur le monde intellectuel. Les journaux étaient déjà bien en main, mais il y avait un groupe de magazines gratuits qui gagnaient de l'argent grâce au "muckraking" - le centre même de la rébellion intellectuelle. Les grandes entreprises s'attaquèrent à ce groupe de magazines gratuits, efficacement, par le biais de la publicité. Les politiques des magazines furent de fait modifiées et les rédacteurs écartés des enquêtes sur les conditions de travail de ces industries... Les écrivains, pour la plupart, ont aussi évolué avec le temps et ont adapté leurs points de vue à la nouvelle demande éditoriale ; les autres ont été réduits au silence ou découragés. L'étape de la carrière littéraire d'Upton Sinclair, qui a immédiatement suivi son immense célébrité en tant qu'auteur de La Jungle, s'inscrit dans cette période où le "muck-raking" était mis hors la loi, et où les éditeurs et les écrivains se retrouvent sous la pression des milieux d'affaires.

Upton Sinclair (1878-1968)

"Sinclair est né à Baltimore, descendant d’une vieille famille sudiste ruinée, mais prétentieuse. « Ce fut mon sort, écrit-il, de vivre dès l’enfance en présence de l’argent des autres. » Élevé par une mère puritaine et un père alcoolique, trimbalé de garni en « saloon », Sinclair, à vingt ans, voit dans l’alcoolisme et la prostitution les deux mamelles du capitalisme. Ce jeune homme ne boit pas, ne danse pas, ne flâne pas, ne mange pas de viande et travaille quatorze heures par jour pour « chasser de son cœur le désir de la Femme ». Il devient socialiste par puritanisme. Parce qu’il voit le monstre qu’est devenu l’Amérique : « l’espoir du genre humain » a failli. Une poignée de grands trusts, Morgan, Carnegie, Rockefeller, tiennent le pays, important une main-d’œuvre servile, entassée dans des taudis. La collusion du « big business » et des milieux politiques, la tradition libérale de non-intervention laissent au capitalisme sauvage les mains libres. Pour obtenir des réformes, il faut mobiliser l’opinion.

Une poignée de journalistes et d’écrivains, les «muckrakers» (remueurs de boue), dont Sinclair devient le chef de file, commencent, au début du siècle, à attaquer les trusts. Instinctivement contestataire, il entre en contact avec les milieux socialistes. Il collabore au McClure’s, journal des « muckrakers ». En 1904, on l’envoie enquêter à Chicago dans les abattoirs du trust Armour. Il en ramène la "Jungle", roman-reportage que le soutien de Jack London permet de publier. Et c’est le scandale et la gloire." (Encycl.Larousse)

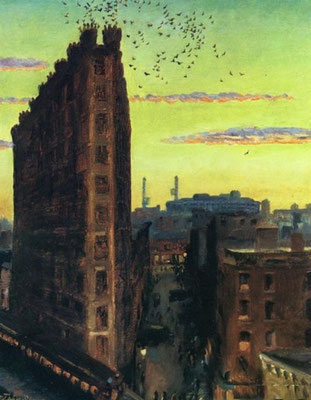

Upton Sinclair introduit ainsi dans le roman le prolétariat industriel et la lutte des classes, et dans son roman le plus célèbre, "La Jungle" (1906) dénonce les conditions de travail dans les abattoirs de Chicago et de la vanité des rêves nourris par les immigrés. Suivent ensuite autant de romans et d'essais de combat qui se veulent, au-delà de la dénonciation de l'exploitation, une pensée politique qui se cherche : "The Metropolis" (1908) attaque la haute société new-yorkaise, "The Money Changers" (1908) les banquiers, "Sylvia’s Marriage" (1914) les maladies vénériennes, "King Coal" (1917) l’industrie des mines, "The Profits of Religion" (1918) la religion, "The Brass Check" (1919) les journaux, "Oil !" (1927) les pétroliers. Le cycle de "Lanny Budd", composé de 1939 à 1949, embrasse en onze romans et 7 364 pages l'histoire du monde de 1913 aux années 1950.

La Jungle (The Jungle, 1906)

"It was four o’clock when the ceremony was over and the carriages began to arrive. There had been a crowd following all the way, owing to the exuberance of Marija Berczynskas. The occasion rested heavily upon Marija’s broad shoulders—it was her task to see that all things went in due form, and after the best home traditions; and, flying wildly hither and thither, bowling every one out of the way, and scolding and exhorting all day with her tremendous voice, Marija was too eager to see that others conformed to the proprieties to consider them herself. She had left the church last of all, and, desiring to arrive first at the hall, had issued orders to the coachman to drive faster. When that personage had developed a will of his own in the matter, Marija had flung up the window of the carriage, and, leaning out, proceeded to tell him her opinion of him, first in Lithuanian, which he did not understand, and then in Polish, which he did. Having the advantage of her in altitude, the driver had stood his ground and even ventured to attempt to speak; and the result had been a furious altercation, which, continuing all the way down Ashland Avenue, had added a new swarm of urchins to the cortege at each side street for half a mile."

Envoyé par le rédacteur en chef du magazine "McCIure`s" pour enquêter sur les conditions de travail dans les abattoirs et les trusts de la viande de Chicago, Sinclair s`y installa en octobre 1904 (suite à une grève des employés ) et, se faisant passer pour un ouvrier. Il accumula pendant sept semaines les données qui allaient lui permettre d'écrire cet ouvrage dont la parution eut d`abord lieu en feuilleton, du 25 février au 4 novembre 1905, dans l'hebdomadaire socialiste "The Appeal to Reason". Et la "Jungle" est d’abord un reportage implacable, brut, dénonçant les conditions humaines et sanitaires de ces abattoirs, ses cadences infernales, son absence d’hygiène et de sécurité, l'exploitation des travailleurs mais aussi la fabrication de conserves avariées. Le reportage à sensation se veut aussi une allégorie naturaliste : Jurgis Rudkus, le héros, est, au début du roman, un homme simple qui a récemment quitté la Lituanie pour gagner un pays plein de promesses et fonder une famille. Mais l’ingénu est brisé par le capitalisme, la puanteur des déchets de l'industrie de la viande et la lutte pour le pain quotidien; invalide, chômeur, il voit sa femme se prostituer, sombre dans l'enfer; le roman se termine sur un espoir, la conversion au socialisme...

C'est donc l`histoire d`une famille d'immigrants lituaniens, et en particulier d`un certain Jurgis Rudkus. Au début, tout va "bien" ou du moins dans l'acceptation d'une certaine normalité : on trime aux abattoirs, dans la puanteur et l'exploitation éhontée; on vit dans des taudis et dans une misère noire; on gèle de froid, mais on travaille dur et honnêtement, et on épouse celle qu'on aime, et on a un enfant...

(I) "It was four o'clock when the ceremony was over and the carriages began to arrive. There had been a crowd following all the way, owing to the exuberance of Marija Berczynskas. The occasion rested heavily upon Marija's broad shoulders—it was her task to see that all things went in due form, and after the best home traditions; and, flying wildly hither and thither, bowling every one out of the way, and scolding and exhorting all day with her tremendous voice, Marija was too eager to see that others conformed to the proprieties to consider them herself. She had left the church last of all, and, desiring to arrive first at the hall, had issued orders to the coachman to drive faster. When that personage had developed a will of his own in the matter, Marija had flung up the window of the carriage, and, leaning out, proceeded to tell him her opinion of him, first in Lithuanian, which he did not understand, and then in Polish, which he did. Having the advantage of her in altitude, the driver had stood his ground and even ventured to attempt to speak; and the result had been a furious altercation, which, continuing all the way down Ashland Avenue, had added a new swarm of urchins to the cortege at each side street for half a mile.

This was unfortunate, for already there was a throng before the door. The music had started up, and half a block away you could hear the dull "broom, broom" of a cello, with the squeaking of two fiddles which vied with each other in intricate and altitudinous gymnastics. Seeing the throng, Marija abandoned precipitately the debate concerning the ancestors of her coachman, and, springing from the moving carriage, plunged in and proceeded to clear a way to the hall. Once within, she turned and began to push the other way, roaring, meantime, "Eik! Eik! Uzdaryk-duris!" in tones which made the orchestral uproar sound like fairy music.

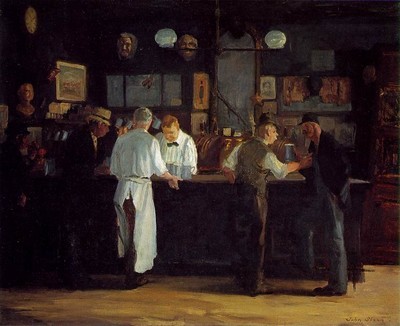

"Z. Graiczunas, Pasilinksminimams darzas. Vynas. Sznapsas. Wines and Liquors. Union Headquarters"—that was the way the signs ran. The reader, who perhaps has never held much converse in the language of far-off Lithuania, will be glad of the explanation that the place was the rear room of a saloon in that part of Chicago known as "back of the yards." This information is definite and suited to the matter of fact; but how pitifully inadequate it would have seemed to one who understood that it was also the supreme hour of ecstasy in the life of one of God's gentlest creatures, the scene of the wedding feast and the joy-transfiguration of little Ona Lukoszaite!"

Au tournant du XXe siècle, Ona Lukoszaite et Jurgis Rudkus, deux immigrants lituaniens arrivés récemment à Chicago (ils sont en tout une famille élargie d'une douzaine de personnes, dont Dede Antanas, son père, Teta Elzbieta, la belle-mère d’Ona, Marija Berczynskas, la cousine d’Ona), se marient, et la célébration a lieu dans un hall près des parcs à bestiaux de Chicago dans une zone de la ville connue sous le nom de Packingtown, le centre de l’industrie de l’emballage de la viande. La nourriture, la bière et la musique remplissent la salle. Suivant la tradition lituanienne, les personnes affamées qui s’attardent à l’entrée sont invitées à manger à leur faim. Les musiciens jouent mal mais, au milieu de la fête générale, personne ne semble s’en soucier. Le point culminant de la célébration est "the acziavimas" au cours de laquelle un cercle se ferme entre les convives, chacun danse avec la mariée et donne sa contribution aux jeunes mariés. Mais beaucoup de ces invités profitent de la situation et les prédateurs sont nombreux. Sinclair est dans la continuité du style journalistique d'un Theodore Dreiser, qui a dénoncé les problèmes sociaux de l’industrialisation, et de Stephen Crane, qui a dépeint les horreurs de la guerre civile, mais son journalisme est celui des faits divers, l'excès de détails est ici destiné plus à faire passer un message qu'à décrire une atmosphère ou planter un décor ...

Pendant la période de l’industrialisation, à la fin du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe siècle, les millions d’immigrants qui affluaient aux États-Unis ont rencontré, outre des conditions de travail et des niveaux salaires désastreux, une lourde hostilité de la part des habitants de leur nouvelle patrie. Leurs pratiques culturelles étaient considérées comme une menace pour la culture traditionnelle américaine et Sinclair doit, dès les premiers chapitres, tenter d'éveiller quelque sympathie de ses lecteurs à l'égard des immigrants lituaniens qu'il met en scène (amour de la tradition, importance de la famille, de la communauté). Il s'attache de même à décrire tous les dangers auxquels ils ont exposés, des dangers qui ne sont que le reflet des valeurs brutales et prédatrices du capitalisme de consommation.

En outre, la famille de Jurgis et Ona immigre en Amérique à la recherche du rêve américain, une Amérique qui s'expose comme la terre de la liberté et de l’opportunité, un mythe qu'incarne dans le chapitre 2 le lituanien Jokubas Szedvilas, épicier, qui prétend avoir fait fortune et qui leur promet que le travail acharné et l’engagement envers les valeurs sociales leur permettra de réussir. Et quand bien même ce rêve semble déjà sérieusement écorné (Jokubas dissimule bien des difficultés financières), Sinclair montre à ses lecteurs américains combien l'immigré Jurgis, dans son innocence valeureuse des premiers temps, révèle une foi débordante d'optimisme dans cette éthique du travail et de l'effort prônée comme une valeur américaine fondamentale ("Leave it to me; leave it to me. I will earn more money - I will work harder.") ....

Chapitre 2, Jokubas conduit Jonas et sa famille vers une pension misérable et surpeuplée gérée par une misérable veuve. Jurgis et Ona s'y installent et découvrent leur nouvel univers, la puanteur de la chair des animaux en décomposition et des excréments d’animaux, la fumée, des dépotoirs à ciel ouvert.. Mais le crépuscule envahit ce spectacle sordide, Packingtown semble alors revêtir les habits de ce rêve, faits d’emploi pour des milliers et des milliers d’hommes, d’opportunité et de liberté, de vie, d’amour et de joie, oui, "Demain, dit Jurgis, je vais y aller et trouver un travail!" ...

"It could not move faster anyhow, on account of the state of the streets. Those through which Jurgis and Ona were walking resembled streets less than they did a miniature topographical map. The roadway was commonly several feet lower than the level of the houses, which were sometimes joined by high board walks; there were no pavements—there were mountains and valleys and rivers, gullies and ditches, and great hollows full of stinking green water. In these pools the children played, and rolled about in the mud of the streets; here and there one noticed them digging in it, after trophies which they had stumbled on. One wondered about this, as also about the swarms of flies which hung about the scene, literally blackening the air, and the strange, fetid odor which assailed one's nostrils, a ghastly odor, of all the dead things of the universe. It impelled the visitor to questions and then the residents would explain, quietly, that all this was "made" land, and that it had been "made" by using it as a dumping ground for the city garbage. After a few years the unpleasant effect of this would pass away, it was said; but meantime, in hot weather—and especially when it rained—the flies were apt to be annoying. Was it not unhealthful? the stranger would ask, and the residents would answer, "Perhaps; but there is no telling."

A little way farther on, and Jurgis and Ona, staring open-eyed and wondering, came to the place where this "made" ground was in process of making. Here was a great hole, perhaps two city blocks square, and with long files of garbage wagons creeping into it. The place had an odor for which there are no polite words; and it was sprinkled over with children, who raked in it from dawn till dark. Sometimes visitors from the packing houses would wander out to see this "dump," and they would stand by and debate as to whether the children were eating the food they got, or merely collecting it for the chickens at home. Apparently none of them ever went down to find out.

Beyond this dump there stood a great brickyard, with smoking chimneys. First they took out the soil to make bricks, and then they filled it up again with garbage, which seemed to Jurgis and Ona a felicitous arrangement, characteristic of an enterprising country like America. A little way beyond was another great hole, which they had emptied and not yet filled up. This held water, and all summer it stood there, with the near-by soil draining into it, festering and stewing in the sun; and then, when winter came, somebody cut the ice on it, and sold it to the people of the city. This, too, seemed to the newcomers an economical arrangement; for they did not read the newspapers, and their heads were not full of troublesome thoughts about "germs."

They stood there while the sun went down upon this scene, and the sky in the west turned blood-red, and the tops of the houses shone like fire. Jurgis and Ona were not thinking of the sunset, however—their backs were turned to it, and all their thoughts were of Packingtown, which they could see so plainly in the distance. The line of the buildings stood clear-cut and black against the sky; here and there out of the mass rose the great chimneys, with the river of smoke streaming away to the end of the world. It was a study in colors now, this smoke; in the sunset light it was black and brown and gray and purple. All the sordid suggestions of the place were gone—in the twilight it was a vision of power. To the two who stood watching while the darkness swallowed it up, it seemed a dream of wonder, with its talc of human energy, of things being done, of employment for thousands upon thousands of men, of opportunity and freedom, of life and love and joy. When they came away, arm in arm, Jurgis was saying, "Tomorrow I shall go there and get a job!"

Les vastes parcs à bestiaux, remplis de bovins, de porcs et de moutons, démontrent la merveilleuse efficacité de la machinerie économique de l’industrie de la viande. Cependant, les animaux entassés dans les parcs à bestiaux et rassemblés pour l’abattage constituent aussi de métaphores soulignant la misérable existence de ces travailleurs immigrés qui se pressent dans Packingtown en quête d'un morceau du rêve américain. Comme ces animaux, comme d'autres immigrants, les Jurgis en toute sont entassés dans la machinerie du capitalisme et massacrés en masse. Sinclair attaque avec virulence la pratique du commerce de la viande, de ces propriétaires d’usine qui valorisent leurs profits sur la santé des travailleurs mais aussi du consommateur, un consommateur-lecteur qui peut ainsi s’identifier au travailleur immigré (chap.6)

"All of these were sinister incidents; but they were trifles compared to what Jurgis saw with his own eyes before long. One curious thing he had noticed, the very first day, in his profession of shoveler of guts; which was the sharp trick of the floor bosses whenever there chanced to come a "slunk" calf. Any man who knows anything about butchering knows that the flesh of a cow that is about to calve, or has just calved, is not fit for food. A good many of these came every day to the packing houses—and, of course, if they had chosen, it would have been an easy matter for the packers to keep them till they were fit for food. But for the saving of time and fodder, it was the law that cows of that sort came along with the others, and whoever noticed it would tell the boss, and the boss would start up a conversation with the government inspector, and the two would stroll away. So in a trice the carcass of the cow would be cleaned out, and entrails would have vanished; it was Jurgis' task to slide them into the trap, calves and all, and on the floor below they took out these "slunk" calves, and butchered them for meat, and used even the skins of them.

One day a man slipped and hurt his leg; and that afternoon, when the last of the cattle had been disposed of, and the men were leaving, Jurgis was ordered to remain and do some special work which this injured man had usually done. It was late, almost dark, and the government inspectors had all gone, and there were only a dozen or two of men on the floor. That day they had killed about four thousand cattle, and these cattle had come in freight trains from far states, and some of them had got hurt. There were some with broken legs, and some with gored sides; there were some that had died, from what cause no one could say; and they were all to be disposed of, here in darkness and silence. "Downers," the men called them; and the packing house had a special elevator upon which they were raised to the killing beds, where the gang proceeded to handle them, with an air of businesslike nonchalance which said plainer than any words that it was a matter of everyday routine. It took a couple of hours to get them out of the way, and in the end Jurgis saw them go into the chilling rooms with the rest of the meat, being carefully scattered here and there so that they could not be identified. When he came home that night he was in a very somber mood, having begun to see at last how those might be right who had laughed at him for his faith in America.."

Quand Jurgis rentra à la maison cette nuit-là, il était d’une humeur très sombre, sa foi en l’Amérique pourrait-elle être ébranlée?

Autre pilier du rêve américain, la maison, le foyer qui abrite la famille, et là aussi Sinclair se livre au même procès, l’arnaque immobilière est permanente et constante. Le capitalisme est bien cette machine qui encourage et valorise la corruption - nous le verrons, quiconque espère progresser doit se corrompre....

Jurgis a donc débuté en balayant les entrailles du bétail abattu et gagne un peu plus de deux dollars pour douze heures de travail, Marija appose des étiquettes sur des cannettes pour près de deux dollars par jour, et l'on refuse dans un premier temps de laisser travailler Teta Elzbieta, Ona ou les enfants. La vie s'écoule, Jurgis assistera religieusement aux réunions syndicales, décidera d’apprendre l’anglais en suivant des cours du soir, et deviendra citoyen américain dans des conditions qui sont loin de correspondre à cette étape tant vantée par le grand rêve américain : on l'incite à devenir américain pour suivre un inconnu dans un isoloir pour deux dollars et participer ainsi, en toute naïveté, à des élections truquées par un vaste stratagème d’achat de votes : les membres de la pègre criminelle de Chicago profitent d’ouvriers ignorants et pauvres pour pervertir le processus démocratique et asseoir politiquement selon des hommes d’affaires complices. En fin de compte, le capitalisme attaque l’idée morale fondamentale qui justifie ce rêve américain, à savoir que le travail dur et honnête gagne sa juste récompense. Sinclair entend démontrer que, dans l’économie capitaliste, on ne peut progresser par le travail acharné et un engagement fort pour de bonnes valeurs sociales. Au lieu de cela, l’individu entreprenant doit devenir un menteur, voleur, et prédateur pour éviter d’être exploité....

Chapitre X, premier tournant, la famille s'est installée, mais les revenus viennent à manquer...

"During the early part of the winter the family had had money enough to live and a little over to pay their debts with; but when the earnings of Jurgis fell from nine or ten dollars a week to five or six, there was no longer anything to spare. The winter went, and the spring came, and found them still living thus from hand to mouth, hanging on day by day, with literally not a month's wages between them and starvation. Marija was in despair, for there was still no word about the reopening of the canning factory, and her savings were almost entirely gone. She had had to give up all idea of marrying then; the family could not get along without her—though for that matter she was likely soon to become a burden even upon them, for when her money was all gone, they would have to pay back what they owed her in board. So Jurgis and Ona and Teta Elzbieta would hold anxious conferences until late at night, trying to figure how they could manage this too without starving..."

L'existence se craquelle, le printemps, l'été, toute la journée les fleuves de sang chaud se déversaient, avec le soleil battant, et l’air immobile, la puanteur était suffisante pour frapper tout un chacun, les hommes qui travaillaient sur les lits d’abattage venaient à puer avec la saleté, et ingérer autant de sang cru que de nourriture au moment du dîner, quand ils étaient au travail, ils ne pouvaient même pas s’essuyer le visage, que ce soit les abattoirs ou les dépotoirs, il n’y avait pas de fuite, les flots de mouches partout, toute une existence attachée à la "great packing machine" ...

"All day long the rivers of hot blood poured forth, until, with the sun beating down, and the air motionless, the stench was enough to knock a man over; all the old smells of a generation would be drawn out by this heat—for there was never any washing of the walls and rafters and pillars, and they were caked with the filth of a lifetime. The men who worked on the killing beds would come to reek with foulness, so that you could smell one of them fifty feet away; there was simply no such thing as keeping decent, the most careful man gave it up in the end, and wallowed in uncleanness. There was not even a place where a man could wash his hands, and the men ate as much raw blood as food at dinnertime. When they were at work they could not even wipe off their faces—they were as helpless as newly born babes in that respect; and it may seem like a small matter, but when the sweat began to run down their necks and tickle them, or a fly to bother them, it was a torture like being burned alive. Whether it was the slaughterhouses or the dumps that were responsible, one could not say, but with the hot weather there descended upon Packingtown a veritable Egyptian plague of flies; there could be no describing this—the houses would be black with them. There was no escaping; you might provide all your doors and windows with screens, but their buzzing outside would be like the swarming of bees, and whenever you opened the door they would rush in as if a storm of wind were driving them.

Perhaps the summertime suggests to you thoughts of the country, visions of green fields and mountains and sparkling lakes. It had no such suggestion for the people in the yards. The great packing machine ground on remorselessly, without thinking of green fields; and the men and women and children who were part of it never saw any green thing, not even a flower. Four or five miles to the east of them lay the blue waters of Lake Michigan; but for all the good it did them it might have been as far away as the Pacific Ocean. They had only Sundays, and then they were too tired to walk. They were tied to the great packing machine, and tied to it for life. The managers and superintendents and clerks of Packingtown were all recruited from another class, and never from the workers; they scorned the workers, the very meanest of them. A poor devil of a bookkeeper who had been working in Durham's for twenty years at a salary of six dollars a week, and might work there for twenty more and do no better, would yet consider himself a gentleman, as far removed as the poles from the most skilled worker on the killing beds; he would dress differently, and live in another part of the town, and come to work at a different hour of the day, and in every way make sure that he never rubbed elbows with a laboring man. Perhaps this was due to the repulsiveness of the work; at any rate, the people who worked with their hands were a class apart, and were made to feel it...."

Le destin de Marija prend aussi un tragique détour, après un travail effectué dans des conditions parfaitement inhuamines, décrites en détail par Sinclair ...

"She was shut up in one of the rooms where the people seldom saw the daylight; beneath her were the chilling rooms, where the meat was frozen, and above her were the cooking rooms; and so she stood on an ice-cold floor, while her head was often so hot that she could scarcely breathe. Trimming beef off the bones by the hundred-weight, while standing up from early morning till late at night, with heavy boots on and the floor always damp and full of puddles, liable to be thrown out of work indefinitely because of a slackening in the trade, liable again to be kept overtime in rush seasons, and be worked till she trembled in every nerve and lost her grip on her slimy knife, and gave herself a poisoned wound—that was the new life that unfolded itself before Marija...".

La "belle histoire" commence à mal tourner, à partir du chapitre XII, tout se dégrade. Jurgis se blesse, perd son travail aux abattoirs, n`en retrouvera qu'à l'usine d'engrais ("À ceux qui sont tombés dans cette catégorie inférieure, il reste une ressource : l'usine d`engrais chimique! ››), et se mettra à boire. ...

Alors qu'Ona met au monde un enfant, Jurgis se blesse et la famille doit envoyer Nikalojus et Vilimas, les fils de dix et onze ans de Teta Elzbieta, travailler comme vendeurs de journaux. Et c'est ainsi que progressivement Sinclair va nous montrer comment le capitalisme va détruire progressivement cette fameuse structure familiale sans laquelle le rêve américain ne peut espérer survivre. Les faibles, les estropiés et les vieux sont éliminés avec une efficacité brutale. Des capitalistes comme ceux qui dirigeaient les parcs à bestiaux de Chicago au début du XXe siècle justifiaient souvent la brutalité de leurs pratiques en termes s'apparentant au fameux darwinisme social, comme dans la nature, où seuls les plus forts sont censés survivre, seuls les riches capitalistes sont considérés comme les plus aptes et la classe ouvrière salariée réduite à une forme inférieure d’humanité. Pour celle-ci le besoin désespéré de subsistance passe tout sentiment familial, la mort de l’infirme Kristoforas, bouche inutile à nourrir, est vécu comme une délivrance. Ona et Jurgis se séparent, et Jurgis sombre dans un alcoolisme endémique, Antanas souffre de malnutrition (chap.14), puis un soir Ona ne rentre pas chez elle, Jurgis découvre le mensonge ..

"He was looking her fairly in the face, and he could read the sudden fear and wild uncertainty that leaped into her eyes. "I - I had to go to - to the store," she gasped, almost in a whisper, "I had to go -".

"You are lying to me," said Jurgis. Then he clenched his hands and took a step toward her. "Why do you lie to me?" he cried, fiercely. "What are you doing that you have to lie to me?" "Jurgis!" she exclaimed, starting up in fright. "Oh, Jurgis, how can you?"

"You have lied to me, I say!" he cried. "You told me you had been to Jadvyga's house that other night, and you hadn't. You had been where you were last night—somewheres downtown, for I saw you get off the car. Where were you?"

It was as if he had struck a knife into her. She seemed to go all to pieces. For half a second she stood, reeling and swaying, staring at him with horror in her eyes; then, with a cry of anguish, she tottered forward, stretching out her arms to him. But he stepped aside, deliberately, and let her fall. She caught herself at the side of the bed, and then sank down, burying her face in her hands and bursting into frantic weeping.

There came one of those hysterical crises that had so often dismayed him. Ona sobbed and wept, her fear and anguish building themselves up into long climaxes. Furious gusts of emotion would come sweeping over her, shaking her as the tempest shakes the trees upon the hills; all her frame would quiver and throb with them—it was as if some dreadful thing rose up within her and took possession of her, torturing her, tearing her. This thing had been wont to set Jurgis quite beside himself; but now he stood with his lips set tightly and his hands clenched—she might weep till she killed herself, but she should not move him this time—not an inch, not an inch. Because the sounds she made set his blood to running cold and his lips to quivering in spite of himself, he was glad of the diversion when Teta Elzbieta, pale with fright, opened the door and rushed in; yet he turned upon her with an oath. "Go out!" he cried, "go out!" And then, as she stood hesitating, about to speak, he seized her by the arm, and half flung her from the room, slamming the door and barring it with a table. Then he turned again and faced Ona, crying—"Now, answer me!"

Yet she did not hear him—she was still in the grip of the fiend. Jurgis could see her outstretched hands, shaking and twitching, roaming here and there over the bed at will, like living things; he could see convulsive shudderings start in her body and run through her limbs. She was sobbing and choking—it was as if there were too many sounds for one throat, they came chasing each other, like waves upon the sea. Then her voice would begin to rise into screams, louder and louder until it broke in wild, horrible peals of laughter. Jurgis bore it until he could bear it no longer, and then he sprang at her, seizing her by the shoulders and shaking her, shouting into her ear: "Stop it, I say! Stop it!"

Ona avoue avoir été violée par un certain Phil Connor, un des patrons de l'usine, l'a forcée à l'accompagner au bordel de Mlle Henderson (chap.15), Jurgis, après avoir tenté d'étrangler Connor, est arrêté et conduit en prison, où crimnels de toutes sortes, innocentes et coupables, partagent les mêmes quartiers sordides. La fureur de Jurgis face à Connor est décrite dans toute sa rage bestiale, l'ouvrier salarié est ainsi porté à une véritable déshumanisation qu'il ne parvient pas à certains moments à canaliser ....

"He ran like one possessed, blindly, furiously, looking neither to the right nor left. He was on Ashland Avenue before exhaustion compelled him to slow down, and then, noticing a car, he made a dart for it and drew himself aboard. His eyes were wild and his hair flying, and he was breathing hoarsely, like a wounded bull; but the people on the car did not notice this particularly—perhaps it seemed natural to them that a man who smelled as Jurgis smelled should exhibit an aspect to correspond. They began to give way before him as usual. The conductor took his nickel gingerly, with the tips of his fingers, and then left him with the platform to himself. Jurgis did not even notice it—his thoughts were far away. Within his soul it was like a roaring furnace; he stood waiting, waiting, crouching as if for a spring.

He had some of his breath back when the car came to the entrance of the yards, and so he leaped off and started again, racing at full speed. People turned and stared at him, but he saw no one—there was the factory, and he bounded through the doorway and down the corridor. He knew the room where Ona worked, and he knew Connor, the boss of the loading-gang outside. He looked for the man as he sprang into the room.

The truckmen were hard at work, loading the freshly packed boxes and barrels upon the cars. Jurgis shot one swift glance up and down the platform—the man was not on it. But then suddenly he heard a voice in the corridor, and started for it with a bound. In an instant more he fronted the boss.

He was a big, red-faced Irishman, coarse-featured, and smelling of liquor. He saw Jurgis as he crossed the threshold, and turned white. He hesitated one second, as if meaning to run; and in the next his assailant was upon him. He put up his hands to protect his face, but Jurgis, lunging with all the power of his arm and body, struck him fairly between the eyes and knocked him backward. The next moment he was on top of him, burying his fingers in his throat."

Jurgis sera condamné à trente jours de prison après un procès qui n'est qu'une vaste farce, la justice, la prison, c'est un autre univers dans lequel nous plonge Sinclair (chap.16, 17). C'est bien l'image de l'impuissance qui transparaît ici, impuissance des plus pauvres face aux prédateurs qui détiennent tout pouvoir sur eux. C'est enfin un système judiciaire totalement perverti par le capitalisme qui nous ici dénoncé avec l’impunité d'hommes tel que Connor et la plongée d'une famille entière dans la précarité avec la condamnation sans concession du chef de famille. Lorsque Jurgis sortira de prison, après être y resté resté trois jours de plus parce qu’il n’a pas l’argent pour payer le coût de son procès, il regagne sa maison de Packingtown et découvre une nouvelle famille vivant qui en a pris possession : les siens ont été expulsés. Nouvelle étape (chap. 19-21), au fond les vagues d’immigrants traversant Packingtown et sa misère ne font que s'exploiter les unes les autres au fur et à mesure de leur intégration, et Sinclair dénonce ici deux aspects bien ambigus de ce capitalisme rayonnant, des lois sur le travail des enfants, qui en fait laissent perdurer l'essentiel du système, et des soit-disantes améliorations des conditions de travail poussées par cette singulière philantropie qui ne changent rien à l'existence : Jurgis trouve travail dans une usine produisant des machines liées à la récolte, le climat est différent mais la cadence et la précarité inchangées. Le pseudo christianisme des philanthropes n'est que moralisme, un moralisme qui ne peut être vécu tant les conditions matérielles sont inacceptables.

A partir du chapitre XXII, nous suivons une nouvelle étape dans la vie de Jurgis : à sa sortie, sa femme accouche d`un bébé mort-né et meurt. Après ce drame, son fils se noie accidentellement dans un caniveau, alors que d'autres enfants dans cette même misère sont dévorés par des rats... Il abandonne sa famille, travaille dans une ferme, gagne Chicago, et sombre dans la précarité en répondant coup pour coup. . Employé comme terrassier, une nouvelle blessure lui interdit définitivement de retrouver un emploi. A l`occasion d`un second séjour en prison, Jurgis entre en contact avec la « haute pègre ›› de Chicago..

Et c'est en intégrant les bas-fonds criminels de la ville, qu'il devient un petit rouage de cette énorme machinerie politique qui vit dans une corruption généralisée. Chapitre 26, Jurgis est ainsi logiquement devenu "briseur de grève", nouveau degré dans la course effrénée à la survie de ce monstre qu'est le capitalisme. Le grand désir de réaliser le rêve américain par des moyens honnêtes est désormais pour Jurgis une parfaite utopie ...

"So Jurgis became one of the new "American heroes," a man whose virtues merited comparison with those of the martyrs of Lexington and Valley Forge. The resemblance was not complete, of course, for Jurgis was generously paid and comfortably clad, and was provided with a spring cot and a mattress and three substantial meals a day; also he was perfectly at ease, and safe from all peril of life and limb, save only in the case that a desire for beer should lead him to venture outside of the stockyards gates. And even in the exercise of this privilege he was not left unprotected; a good part of the inadequate police force of Chicago was suddenly diverted from its work of hunting criminals, and rushed out to serve him. The police, and the strikers also, were determined that there should be no violence; but there was another party interested which was minded to the contrary—and that was the press. On the first day of his life as a strikebreaker Jurgis quit work early, and in a spirit of bravado he challenged three men of his acquaintance to go outside and get a drink. They accepted, and went through the big Halsted Street gate, where several policemen were watching, and also some union pickets, scanning sharply those who passed in and out. Jurgis and his companions went south on Halsted Street; past the hotel, and then suddenly half a dozen men started across the street toward them and proceeded to argue with them concerning the error of their ways. As the arguments were not taken in the proper spirit, they went on to threats; and suddenly one of them jerked off the hat of one of the four and flung it over the fence. The man started after it, and then, as a cry of "Scab!" was raised and a dozen people came running out of saloons and doorways, a second man's heart failed him and he followed. Jurgis and the fourth stayed long enough to give themselves the satisfaction of a quick exchange of blows, and then they, too, took to their heels and fled back of the hotel and into the yards again. Meantime, of course, policemen were coming on a run, and as a crowd gathered other police got excited and sent in a riot call. Jurgis knew nothing of this, but went back to "Packers' Avenue," and in front of the "Central Time Station" he saw one of his companions, breathless and wild with excitement, narrating to an ever growing throng how the four had been attacked and surrounded by a howling mob, and had been nearly torn to pieces. While he stood listening, smiling cynically, several dapper young men stood by with notebooks in their hands, and it was not more than two hours later that Jurgis saw newsboys running about with armfuls of newspapers, printed in red and black letters six inches high:

VIOLENCE IN THE YARDS! STRIKEBREAKERS SURROUNDED BY FRENZIED MOB!

If he had been able to buy all of the newspapers of the United States the next morning, he might have discovered that his beer-hunting exploit was being perused by some two score millions of people, and had served as a text for editorials in half the staid and solemn business-men's newspapers in the land."

Chapitre XXVII, le monde tourne, les grèves s'achèvent, Jurgis est en quête de petits emplois, la course à la survie reprend. Il rencontre sur son chemin Marija, qui désormais se prostitue et se drogue. Tout au long du roman, des vies humaines sont achetées et vendues, et la plupart des ouvriers salariés ne réalisent même pas qu’ils font partie d’un vaste marché de chair humaine. "La Jungle" : le monde de l’ouvrier salarié est un royaume sauvage caractérisé par une lutte darwinienne pour la survie. Ceux qui refusent de sacrifier leur humanité, leur intégrité et leur individualité ne survivent pas, encore moins réussissent, dans ce monde. Les nouveaux arrivants entrent dans cette jungle remplie de prédateurs attendant de les exploiter à chaque tournant. Les structures du capitalisme ne sont qu'une jungle de recoins cachés, chacun contenant ses codes et ses particularités, de l'usine à l'agence immobilière, de la salle d’audience à la prison, des réunions syndicales aux isoloirs des bureaux de vote. C'est alors qu'au chapitre 28, Sinclair, après parcouru tous les maux du capitalisme, fait entrer Jurgis dans une réunion politique jugée décisive : le socialisme va s'imposer comme solution aux problèmes que les vingt-sept premiers chapitres du roman ont explorés en détail. Pour la première fois, dans cette vaste jungle qu'est l'Amérique, Jurgis ne va plus se sentre seul, la poursuite du rêve américain peut reprendre dans une nouvelle ferveur quasi religieuse, sous les traits de l'orateur Ostrinski, un socialiste qui parle lituanien...

"The man had gone back to a seat upon the platform, and Jurgis realized that his speech was over. The applause continued for several minutes; and then some one started a song, and the crowd took it up, and the place shook with it. Jurgis had never heard it, and he could not make out the words, but the wild and wonderful spirit of it seized upon him—it was the "Marseillaise!" As stanza after stanza of it thundered forth, he sat with his hands clasped, trembling in every nerve. He had never been so stirred in his life—it was a miracle that had been wrought in him. He could not think at all, he was stunned; yet he knew that in the mighty upheaval that had taken place in his soul, a new man had been born. He had been torn out of the jaws of destruction, he had been delivered from the thraldom of despair; the whole world had been changed for him—he was free, he was free! Even if he were to suffer as he had before, even if he were to beg and starve, nothing would be the same to him; he would understand it, and bear it. He would no longer be the sport of circumstances, he would be a man, with a will and a purpose; he would have something to fight for, something to die for, if need be! Here were men who would show him and help him; and he would have friends and allies, he would dwell in the sight of justice, and walk arm in arm with power.

L’audience s’est encore calmée, et Jurgis s’est assis. Le président de la réunion s’est avancé et a commencé à parler. Sa voix semblait mince et futile après celle de l’autre, et pour Jurgis, cela semblait une profanation. Pourquoi quelqu’un d’autre devrait-il parler, après cet homme miraculeux—pourquoi ne devraient-ils pas tous s’asseoir en silence? Le président expliquait qu’une collecte serait maintenant utilisée pour couvrir les dépenses de la réunion, et pour le bénéfice du fonds de campagne du parti. Jurgis entendit ; mais il n’avait pas un sou à donner, et ainsi ses pensées allaient ailleurs encore.

Il gardait les yeux fixés sur l’orateur, assis dans un fauteuil, la tête appuyée sur sa main et son attitude indiquant l’épuisement. Mais soudain, il se leva de nouveau, et Jurgis entendit le président de la réunion dire que l’orateur répondrait maintenant à toutes les questions que l’auditoire pourrait vouloir lui poser. L’homme se présenta, et une femme se leva et demanda au Président ce qu’il pensait de Tolstoï. Jurgis n’avait jamais entendu parler de Tolstoï, et ne se souciait pas de lui. Pourquoi voudrait-on poser de telles questions, après une telle adresse? Il ne s’agissait pas de parler, mais de faire ; il s’agissait de se montrer audacieux envers les autres et de les réveiller, de les organiser et de se préparer au combat ! Mais la discussion a continué, sur des tons ordinaires de conversation, et a ramené Jurgis dans le monde quotidien. Il y a quelques minutes, il avait eu envie de saisir la main de la belle dame à ses côtés, et de l’embrasser ; il avait eu envie de jeter ses bras autour du cou de l’homme de l’autre côté de lui. Et maintenant, il a commencé à se rendre compte à nouveau qu’il était un "clochard", qu’il était déchiqueté et sale, qu’il sentait mauvais, et qu’il n’avait nulle part où dormir cette nuit-là!

"The audience subsided again, and Jurgis sat back. The chairman of the meeting came forward and began to speak. His voice sounded thin and futile after the other's, and to Jurgis it seemed a profanation. Why should any one else speak, after that miraculous man—why should they not all sit in silence? The chairman was explaining that a collection would now be taken up to defray the expenses of the meeting, and for the benefit of the campaign fund of the party. Jurgis heard; but he had not a penny to give, and so his thoughts went elsewhere again.

He kept his eyes fixed on the orator, who sat in an armchair, his head leaning on his hand and his attitude indicating exhaustion. But suddenly he stood up again, and Jurgis heard the chairman of the meeting saying that the speaker would now answer any questions which the audience might care to put to him. The man came forward, and some one—a woman—arose and asked about some opinion the speaker had expressed concerning Tolstoy. Jurgis had never heard of Tolstoy, and did not care anything about him. Why should any one want to ask such questions, after an address like that? The thing was not to talk, but to do; the thing was to get bold of others and rouse them, to organize them and prepare for the fight! But still the discussion went on, in ordinary conversational tones, and it brought Jurgis back to the everyday world. A few minutes ago he had felt like seizing the hand of the beautiful lady by his side, and kissing it; he had felt like flinging his arms about the neck of the man on the other side of him. And now he began to realize again that he was a "hobo," that he was ragged and dirty, and smelled bad, and had no place to sleep that night!"

C'est pour Jurgis un choc quasi existentiel, le message est une révélation : mais que faire de cette révélation, de cette soudaine prise de conscience de tout ce qu'il a pu vivre et soudainement réinterprété dans une toute autre perspective, la lumière après l'obscurité. Les derniers chapitres seront donc consacrés au processus de conversion de Jurgis au socialisme sous la conduite de deux personnages, Ostrinski et Schliemann. On a pu, non sans raison, trouver bien des faiblesses à cette toute dernière partie. Mais la force d'évocation, dont les célèbres descriptions de la vie dans les abattoirs, est véritablement dantesque : "The Jungle" reste une œuvre maîtresse du naturalisme social et un sommet du roman à thèse.

Stephen Crane (1871-1900)

Stephen Crane est devenu un auteur "classique" de la littérature américaine, pionnier du roman réaliste américain et précurseur des Frank Norris, T. Dreiser, et plus tard, d’Hemingway. Sa brève existence a alimenté bien des biographies, et sous la précision des détails, la concision de son écriture, la critique a su mettre en valeur le désespoir devant l’absurde de la vie, que seules contrebalancent la solidarité et la maîtrise de soi.

Quatorzième enfant d’un pasteur méthodiste et d’une militante de la Ligue antialcoolique, Stephen Crane est un esprit rebelle qui vécu une enfance marquée par le zèle religieux, la charité, la rédemption. Devenu orphelin, il abandonne ses études et, subsistant misérablement comme reporter franc-tireur en 1892, enquête sur les bas-fonds de New York, où il réunit la documentation de son premier roman, "Maggie, a Girl of the Streets" (Maggie, fille des rues). "The Red Badge of Courage" (1895) évoque avec réalisme et déterminisme un soldat anonyme pris dans une guerre, la guerre de Sécession, qu'il ne comprend pas. Ce roman fait de Crane, pour la critique, un précurseur d'Hemingway et des écrivains de la "génération perdue". La nouvelle "The Open Boat" (1898) est inspirée par son naufrage au cours d’un reportage sur la rébellion cubaine de 1897. Sa méthode documentaire est fondatrice.Correspondant de guerre en Grèce, lors du conflit gréco-turc de 1897, puis à Cuba, lors de la guerre hispano-américaine de 1898, il aggrave sa tuberculose, et après avoir vécu quelque temps en Angleterre, il meurt en Allemagne le 5 juin 1900, à 29 ans.

Maggie, fille des rues (Maggie, a Girl of the Streets, 1893)

"A very little boy stood upon a heap of gravel for the honor of Rum Alley. He was throwing stones at howling urchins from Devil's Row who were circling madly about the heap and pelting at him. His infantile countenance was livid with fury. His small body was writhing in the delivery of great, crimson oaths.

"Run, Jimmie, run! Dey'll get yehs," screamed a retreating Rum Alley child.

"Naw," responded Jimmie with a valiant roar, "dese micks can't make me run."

Howls of renewed wrath went up from Devil's Row throats. Tattered gamins on the right made a furious assault on the gravel heap. On their small, convulsed faces there shone the grins of true assassins. As they charged, they threw stones and cursed in shrill chorus."

Premier roman de Crane, "Maggie, a Girl of the Streets" décrit les étapes, avec une objectivité apparente, de la déchéance fatale d’une fille du peuple : née dans un milieu très pauvre, Maggie fuit l’horreur de l’usine pour être séduite par un barman, puis abandonnée, rejetée par sa famille et la morale conventionnelle, souillée par la corruption et la vénalité urbaines, se prostitue, puis se suicide en se noyant dans l’East River. Le roman passa inaperçu lors de sa publication, mais la critique en fit tardivement un chef-d’œuvre naturaliste naturaliste après son remaniement en 1896.

(XVI) "Pete did not consider that he had ruined Maggie. If he had thought that her soul could never smile again, he would have believed the mother and brother, who were pyrotechnic over the affair, to be responsible for it.

Besides, in his world, souls did not insist upon being able to smile. "What deh hell?"

He felt a trifle entangled. It distressed him. Revelations and scenes might bring upon him the wrath of the owner of the saloon, who insisted upon respectability of an advanced type.

"What deh hell do dey wanna raise such a smoke about it fer?" demanded he of himself, disgusted with the attitude of the family. He saw no necessity for anyone's losing their equilibrium merely because their sister or their daughter had stayed away from home.

Searching about in his mind for possible reasons for their conduct, he came upon the conclusion that Maggie's motives were correct, but that the two others wished to snare him. He felt pursued.

The woman of brilliance and audacity whom he had met in the hilarious hall showed a disposition to ridicule him.

"A little pale thing with no spirit," she said. "Did you note the expression of her eyes? There was something in them about pumpkin pie and virtue. That is a peculiar way the left corner of her mouth has of twitching, isn't it? Dear, dear, my cloud-compelling Pete, what are you coming to?"

Pete asserted at once that he never was very much interested in the girl. The woman interrupted him, laughing.

"Oh, it's not of the slightest consequence to me, my dear young man. You needn't draw maps for my benefit. Why should I be concerned about it?"

But Pete continued with his explanations. If he was laughed at for his tastes in women, he felt obliged to say that they were only temporary or indifferent ones.

The morning after Maggie had departed from home, Pete stood behind the bar. He was immaculate in white jacket and apron and his hair was plastered over his brow with infinite correctness. No customers were in the place. Pete was twisting his napkined fist slowly in a beer glass, softly whistling to himself and occasionally holding the object of his attention between his eyes and a few weak beams of sunlight that had found their way over the thick screens and into the shaded room.

With lingering thoughts of the woman of brilliance and audacity, the bartender raised his head and stared through the varying cracks between the swaying bamboo doors. Suddenly the whistling pucker faded from his lips. He saw Maggie walking slowly past. He gave a great start, fearing for the previously-mentioned eminent respectability of the place.

He threw a swift, nervous glance about him, all at once feeling guilty. No one was in the room.

He went hastily over to the side door. Opening it and looking out, he perceived Maggie standing, as if undecided, on the corner. She was searching the place with her eyes.

As she turned her face toward him Pete beckoned to her hurriedly, intent upon returning with speed to a position behind the bar and to the atmosphere of respectability upon which the proprietor insisted.

Maggie came to him, the anxious look disappearing from her face and a smile wreathing her lips.

"Oh, Pete—," she began brightly.

The bartender made a violent gesture of impatience.

"Oh, my Gawd," cried he, vehemently. "What deh hell do yeh wanna hang aroun' here fer? Do yeh wanna git me inteh trouble?" he demanded with an air of injury.

Astonishment swept over the girl's features. "Why, Pete! yehs tol' me—"

Pete glanced profound irritation. His countenance reddened with the anger of a man whose respectability is being threatened.

"Say, yehs makes me tired. See? What deh hell deh yeh wanna tag aroun' atter me fer? Yeh'll git me inteh trouble wid deh ol' man an' dey'll be hell teh pay! If he sees a woman roun' here he'll go crazy an' I'll lose me job! See? Yer brudder come in here an' raised hell an' deh ol' man hada put up fer it! An' now I'm done! See? I'm done."

The girl's eyes stared into his face. "Pete, don't yeh remem—"

"Oh, hell," interrupted Pete, anticipating.

The girl seemed to have a struggle with herself. She was apparently bewildered and could not find speech. Finally she asked in a low voice: "But where kin I go?"

The question exasperated Pete beyond the powers of endurance. It was a direct attempt to give him some responsibility in a matter that did not concern him. In his indignation he volunteered information.

"Oh, go teh hell," cried he. He slammed the door furiously and returned, with an air of relief, to his respectability.

Maggie went away.

She wandered aimlessly for several blocks. She stopped once and asked aloud a question of herself: "Who?"

A man who was passing near her shoulder, humorously took the questioning word as intended for him.

"Eh? What? Who? Nobody! I didn't say anything," he laughingly said, and continued his way.

Soon the girl discovered that if she walked with such apparent aimlessness, some men looked at her with calculating eyes. She quickened her step, frightened. As a protection, she adopted a demeanor of intentness as if going somewhere.

After a time she left rattling avenues and passed between rows of houses with sternness and stolidity stamped upon their features. She hung her head for she felt their eyes grimly upon her.

Suddenly she came upon a stout gentleman in a silk hat and a chaste black coat, whose decorous row of buttons reached from his chin to his knees. The girl had heard of the Grace of God and she decided to approach this man.

His beaming, chubby face was a picture of benevolence and kind-heartedness. His eyes shone good-will.

But as the girl timidly accosted him, he gave a convulsive movement and saved his respectability by a vigorous side-step. He did not risk it to save a soul. For how was he to know that there was a soul before him that needed saving?

La Conquête du courage (The Red Badge of Courage, 1895)

"The cold passed reluctantly from the earth, and the retiring fogs revealed an army stretched out on the hills, resting. As the landscape changed from brown to green, the army awakened, and began to tremble with eagerness at the noise of rumors. It cast its eyes upon the roads, which were growing from long troughs of liquid mud to proper thoroughfares. A river, amber-tinted in the shadow of its banks, purled at the army's feet; and at night, when the stream had become of a sorrowful blackness, one could see across it the red, eyelike gleam of hostile camp-fires set in the low brows of distant hills."

Publiée en 1895, la "Conquête du courage" évoque, au travers d'une bataille de la guerre de Sécession, première guerre moderne, la bataille de Chancellorsville, vécue par un jeune soldat, la peur devant la cruauté des combats, l'absurdité d'un monde incompréhensible : blessé par les siens, commandé par un officier qui bafouille, le soldat se retrouve finalement, après plusieurs jours de combat, à son point de départ. La conclusion du roman met en exergue la camaraderie des hommes face aux forces déchaînées de l’absurde.

"... Mais subitement des cris étonnés éclatèrent le long des rangs du régiment des novices : « Les voilà qui arrivent encore ! Les voilà qui arrivent encore ! »

L’homme qui se prélassait au sol se remit debout en lâchant : « Seigneur ! »

L’adolescent jeta des regards rapides sur les champs. Il distinguait des formes qui s’élargissaient en masses depuis les bois distants. Il revit l’étendard penché qui courait sus devant. Les obus qui pour un temps avaient cessé d’inquiéter le régiment, vinrent tournoyer encore ; ils éclataient sur les champs et au pied des arbres en farouches éclosions qui jaillissaient comme des fleurs guerrières. Les hommes gémissaient. La joie disparue de leurs regards. Leurs visages souillés exprimaient maintenant un profond dépit. Leurs corps raidis bougeaient avec lenteur, et ils fixaient la frénétique approche de l’ennemi d’un air sombre.

Esclaves qui peinaient à mort dans le temple du dieu Mars, ils commençaient à ressentir de la révolte contre les rudes tâches qu’il leur imposait.

Ils se plaignaient et s’inquiétaient : « Oh ! ç’en est trop ! Pourquoi n’envoie ton pas des renforts ? »

–«On va jamais t’nir cette deuxième volée. Je ne suis pas venu ici pour me battre contre toute la damnée armée rebelle ! » Quelqu’un jeta un cri plaintif : « J’aurais souhaité que Bill Smithers me marche sur les doigts, plutôt que moi sur les siens. »

Les jointures endolories du régiment craquèrent quand il se jeta péniblement en position pour repousser l’assaut. L’adolescent avait le regard fixe. Sûrement, pensa-t-il, cette chose impossible n’allait pas se produire. Il s’attendait à ce que l’ennemi subitement s’arrête, et se retire en s’inclinant jusqu’à terre en guise d’excuse. Tout cela était une erreur. Mais le tir commença quelque part sur la ligne de front, et se propagea comme une longue déchirure des deux côtés opposés. Les flammèches horizontales des tirs produisaient de grands nuages de fumée, qui retombaient en se balançant un moment sous la brise, tout près du sol, puis roulaient à travers les rangs comme par des ouvertures. Les rayons du soleil les teintaient d’ocre jaune, et l’ombre d’un bleu triste. Le drapeau était par moment avalé par cette masse vaporeuse, mais le plus souvent il rejaillissait, resplendissant sous le soleil. L’adolescent avait le regard d’un cheval fourbu. Sa nuque tremblait de fatigue nerveuse, et les muscles de ses bras étaient engourdis et comme exsangues. Ses mains aussi paraissaient grandes et maladroites, comme s’il portait des mitaines invisibles.

Et il y avait une grande incertitude quant à ses genoux. Les paroles dites par ce camarade juste avant d’ouvrir le feu, commençaient à lui revenir : « Oh ! dit, c’en est trop ! Pour qui nous prennent-ils ?… pourquoi qu’on ne nous envoie pas de renforts… J’suis pas ici pour me battre contre toute la damnée armée rebelle. »

Il commençait à exagérer l’endurance, l’habilité et la valeur de l’ennemi qui arrivait. Vacillant presque de fatigue, il s’étonnait au-delà de toute mesure devant une telle insistance au combat. Comme s’ils dussent être des machines d’acier. Il était déprimant de lutter contre de telles choses, condamnés, peut-être, à se battre jusqu’au coucher du soleil. Il leva doucement son fusil, et après un coup d’œil sur la masse éparpillée sur les champs, tira sur un groupe qui avançait au pas de course.

Alors il s’arrêta et, autant qu’il le pouvait, se mit à scruter la fumée. Il eut une vue changeante de terrains couverts d’hommes, qui couraient en hurlant comme de petits diables pris en chasse. Pour l’adolescent, c’était là un assaut de dragons redoutables. Il devenait comme cet homme du conte qui perdait ses jambes à l’approche du monstre rouge et vert. Il restait dans une sorte d’écoute horrifiée. Il paraissait fermer les yeux, attendant d’être avalé.

Un homme à ses côtés, qui jusqu’à présent avait actionné son fusil avec fièvre, s’arrêta soudain et se mit à fuir avec les hauts cris. Un jeune homme dont le visage portait une expression de courage exalté, – la majesté de celui qui ne craint pas de donner sa vie –, fût en un instant frappé d’abjection. Il blêmit comme quelqu’un qui soudain prend conscience qu’il se trouve au bord d’une falaise à minuit. Ce fût une révélation. Lui aussi jeta son arme à terre et prit la fuite. Son visage ne portait nulle honte. Il détala comme un lièvre.

D’autres commencèrent à se défiler sous la fumée. L’adolescent tourna la tête, et, sortant de sa transe, – à ce mouvement qui lui donnait l’impression que le régiment l’abandonnait –, vit les quelques silhouettes qui fuyaient. .. "

Jacob Riis (1849-1914)

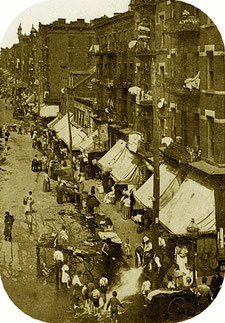

Emigré danois, Riis est photographe et journaliste au New York Tribune de 1877 à 1888, et va capturer dans les taudis new-yorkais du Lower East Side ses matériaux à sensation : il découvre l'impact de la photographie sur le public fortuné et son fameux ouvrage "How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York" (1890) alimentera non seulement le journalisme muckraking, mais fera des émules, tel Jack London qui vécut quelques mois à Londres, dans le quartier malfamé de l'East End, pour publier en 1903 "The People of the Abyss".

" Long ago it was said that " one half of the world does not know how the other half lives." That was true then. It did not know because it did not care. The half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath, so long as it was able to hold them there and keep its own seat. There came a time when the discomfort and crowding below were so great, and the consequent upheavals so violent, that it was no longer an easy thing to do, and then the upper half fell to inquiring what was the matter. Information on the subject has been accumulating rapidly since, and the whole world has had its hands full answering for its old ignorance. In Xew York, the youngest of the world's great cities, that time came later than elsewhere, because the crowding had not been so great. There were those who believed that it would never come ; but their hopes were vain..."

Jacob A. Riis, "The battle with the slum", 1902

Il y a trois ans, écrit dans sa préface Riis, j'ai publié sous le titre "A Ten Years' War" une série d'articles destinés à rendre compte de la bataille entamée contre le système du "bidonville" (slum) avec "How the Other Half Lives". Beaucoup de choses peuvent se passer en trois trois ans, beaucoup d'évènements se sont produits, mais en fin de compte, nous n'avons pas plus progressé pendant ces trois années que pendant les trente années précédentes...

Le bidonville est aussi vieux que la civilisation. La civilisation implique une course, pour aller de l'avant. Dans une course, il y a généralement des gens qui, pour une raison ou pour une autre, ne peuvent pas suivre, ou sont écartés de leurs compagnons. Ils prennent du retard, et lorsqu'ils sont laissés loin derrière, ils perdent espoir et ambition, et abandonnent. Dès lors, s'ils sont laissés à leurs propres ressources, ils sont les victimes, et non les maîtres, de leur environnement, et c'est un mauvais maître. Ils s'entraînent mutuellement toujours plus bas. Le mauvais environnement devient l'hérédité de la génération suivante. Puis, étant donné la foule, vous avez le bidonville tout fait. La bataille contre le bidonville a commencé le jour où la civilisation a reconnu en lui son ennemi. C'était un combat perdu d'avance jusqu'à ce que la conscience s'allie à la peur et à l'intérêt personnel pour le combattre....

"THE slum is as old as civilization. Civilization implies a race, to get ahead. In a race there are usually some who for one cause or another cannot keep up, or are thrust out from among their fellows. They fall behind, and when they have been left far in the rear they lose hope and ambition, and give up. Thenceforward, if left to their own resources, they are the victims, not the masters, of their environment; and it is a bad master. They drag one another always farther down. The bad environment becomes the heredity of the next generation. Then, given the crowd, you have the slum ready-made.

The battle with the slum began the day civilization recognized in it her enemy. It was a losing fight until conscience joined forces with fear and self-interest against it. When common sense and the golden rule obtain among men as a rule of practice, it will be over. The two have not always been classed together, but here they are plainly seen to be allies. Justice to the individual is accepted in theory as the only safe groundwork of the commonwealth. When it is practiced in dealing with the slum, there will shortly be no slum. We need not wait for the millennium, to get rid of it. We can do it now. All that is required is that it shall not be left to itself. That is justice to it and to us, since its grievous ailment is that it cannot help itself. When a man is drowning, the thing to do is to pull him out of the water; afterward there will be time for talking it over. We got at it the other way in dealing with our social problems. The doctrinaires had their day, and they decided to let bad enough alone ; that it was unsafe to interfere with “ causes that operate sociologically,” as one survivor of these unfittest put it to me. It was a piece of scientific humbug that cost the age which listened to it dear. “ Causes that operate sociologically ” are the opportunity of the political and every other kind of scamp who trades upon the depravity and helplessness of the slum, and the refuge of the pessimist who is useless in the fight against them. We have not done yet paying the bills he ran up for us. Some time since we turned to, to pull the drowning man out, and it was time. A little while longer, and we should have been in danger of being dragged down with him.

The slum complaint had been chronic in all ages, but the great changes which the nineteenth century saw, the new industry, political freedom, brought on an acute attack which threatened to become fatal. Too many of us had supposed that, built as our commonwealth was on universal suffrage, it would be proof against the complaints that harassed older states; but in fact it turned out that there was extra hazard in that. Having solemnly resolved that all men are created equal and have certain inalienable rights, among them life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, we shut our eyes and waited for the formula to work. It was as if a man with a cold should take the doctor’s prescription to bed with him, expecting it to cure him. The formula was all right, but merely repeating it worked no cure. When, after a hundred years, we opened our eyes, it was upon sixty cents a day as the living wage of the workingwoman in our cities ; upon “ knee pants ” at forty cents a dozen for the making; upon the Potter’s Field taking tithe of our city life, ten per cent each year for the trench, truly the Lost Tenth of the slum. Our country had grown great and rich ; through our ports was poured food for the millions of Europe. But in the back streets multitudes huddled in ignorance and want. The foreign oppressor had been vanquished, the fetters stricken from the black man at home ; but his white brother, in his bitter plight, sent up a cry of distress that had in it a distinct note of menace. Political freedom we had won; but the problem of helpless poverty, grown vast with the added offscourings of the Old World, mocked us, unsolved. Liberty at sixty cents a day set presently its stamp upon the government of our cities, and it became the scandal and the peril of our political system.

Notre pays était devenu grand et riche ; par nos ports était déversée la nourriture pour les millions d'Européens. Mais dans les ruelles, des multitudes se blottissaient dans l'ignorance et le besoin. L'oppresseur étranger avait été vaincu, l'homme noir avait été libéré de ses chaînes au pays, mais son frère blanc, dans sa situation amère, poussait un cri de détresse qui comportait une note distincte de menace. Nous avions conquis la liberté politique, mais le problème de la pauvreté sans défense, qui s'était amplifié avec l'arrivée de l'ancien monde, se moquait de nous, sans solution. La liberté à soixante cents par jour s'est imposée au gouvernement de nos villes, et elle est devenue le scandale et le péril de notre système politique....